Zoltán Kodály is known for his lifelong study of Hungarian folk music and for writing compositions for classical instruments inspired by these folk traditions. He was born in Kecskemét, Hungary on December 16, 1882 and died in Budapest on March 6, 1967. Dances of Galánta recalls the time he spent in the town of Galánta as a young boy. He called this time “the best seven years of my childhood.” Galánta is a village in what was northern Hungary, now Slovakia, that had a town band lead by a famous gypsy fiddler, Mihok. This band published several volumes of Hungarian dances in Vienna in 1800 that were credited to “several gypsies in Galánta.” The sounds Kodály remembered from childhood came to fruition in a composition forty years later.

Dances of Galánta was composed in 1933 for the 80th anniversary of the Budapest Philharmonic Society. It is scored for two flutes, the second flute doubling piccolo. This part is about 95% piccolo with approximately three lines scored for flute. This colorful work features brilliant wind writing throughout and bravura string tutti passagework.

The work is a symphonic poem in rondo form with alternating slow and fast dances. The solo clarinet melody (which is played by the piccolo as part of the tutti theme at bar 151) acts as the ritornello theme. This melody, along with many of the tunes in the work, are dance melodies known as verbunkos, from the German Werbung (recruitment). At the time the Austrian army recruiters traveled with performers who played these melodies to attract attention and encourage young men to enlist. These melodies became an important part of Hungarian musical traditions in the 19th century. The Brahms Hungarian Dances incorporates melodies in the verbunkos style as well.

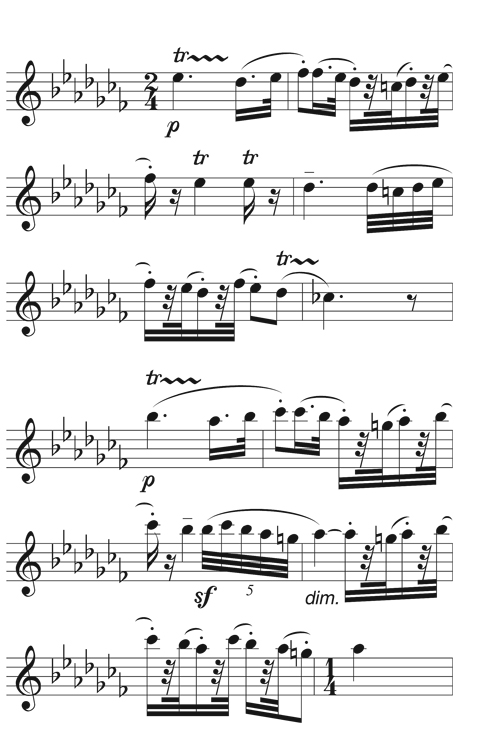

Kodály arranges the dance melodies in sequences of alternating moods and tempos. The allegretto moderato just before 100 begins with the principal flute playing a new and lively theme, answered by the piccolo and flute together at the octave. The piccolo and flute then have a quirky passage where they seem to play the same theme in the wrong key for a few bars just before 125.

Kodály may be mimicking the sounds of more primitive folk instruments. When performing this passage, keep the rhythm graceful and count the rests accurately. The music must move forward. Both of the trills are half-steps. The 32nd notes should remain quick, but not abrupt and short like a Scottish snap rhythm.

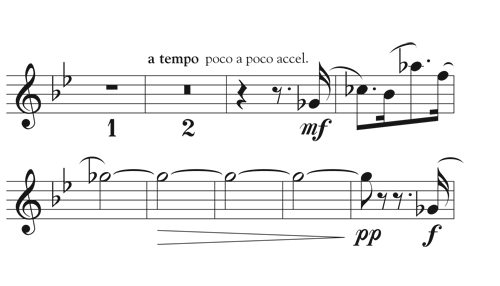

The second half of this work abandons the rondo style and presents a string of dance melodies, one after another, with the exception of one slower melody that accelerates as time goes on. The transition to the final vivace begins in about bar 390 with a piccolo solo, in canon with principal bassoon.

Be sure to match pitch on the long G flat as you will hold this in octaves with the bassoon. Practice long tones with a diminuendo on all pitches in the middle octave as preparation for this orchestral moment. The passage happens twice with a slight harmonic change the second time.

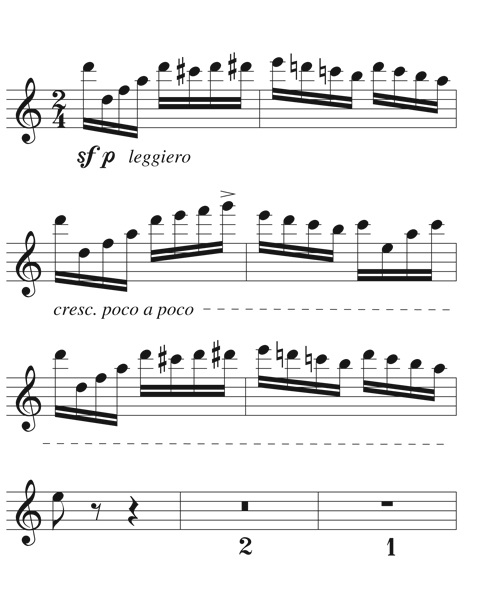

The final vivace contains many bravura passages for the ensemble, and the piccolo becomes the top voice in the orchestral texture. There are plenty of fast double-tongued passages, and a notable passage at bar 551 where the piccolo player leads the orchestra in the stringendo.

I like to practice passages like this all slurred (to assure even finger technique) and then slur 2/tongue 2, and finally, all tongued. The tempo is quarter = 152-160, so be prepared to move.

There is a similar passage at measure 561 where the piccolo is the top voice in the orchestration and there is a stringendo, so watch the conductor carefully and be ready to accelerate. Because the music is written in the style of gypsy fiddling, it has many syncopated rhythms, mood and tempo shifts, and is flashy and fun to play. It is similar to the character of an encore piece, but at 16 minutes in length, it is much longer in scope.