.jpg) When I first became interested in classical music I was initially drawn, as many teenagers are, to music of the Romantic period. I remember being disappointed to discover the paucity of flute solo and chamber works by the great Romantic composers. I gradually came to terms with the fact that the best Romantic flute repertoire is, with a few notable exceptions, in the symphonic literature. Among those wonderful moments when the flute’s haunting voice takes center stage is the solo from the last movement of Brahms’ Symphony #4.

When I first became interested in classical music I was initially drawn, as many teenagers are, to music of the Romantic period. I remember being disappointed to discover the paucity of flute solo and chamber works by the great Romantic composers. I gradually came to terms with the fact that the best Romantic flute repertoire is, with a few notable exceptions, in the symphonic literature. Among those wonderful moments when the flute’s haunting voice takes center stage is the solo from the last movement of Brahms’ Symphony #4.

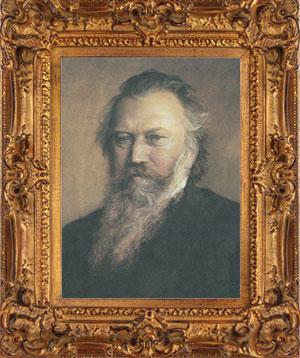

Johannes Brahms is often described as one of the most conservative composers of the nineteenth century. He began writing symphonies relatively late in life; he completed his First Symphony in 1876 at the age of 43, an age when Beethoven had already finished eight of his nine symphonies. His Fourth Symphony was completed in 1885. While some view his music as old-fashioned (for late nineteenth century), others celebrate the way he breathed new life into the forms of the Classical period. In the case of the Finale of his Fourth Symphony, he goes even farther back to the Baroque form of the passacaglia. Brahms constructed the entire movement as a set of variations on the opening eight-bar ground yet maintains the momentum of an exciting symphonic finale. One of the ways he achieves his sense of forward movement is by avoiding constant V-I progressions. The first statement ends with an augmented 6th chord, and many statements end on chords other than the tonic.

Johannes Brahms is often described as one of the most conservative composers of the nineteenth century. He began writing symphonies relatively late in life; he completed his First Symphony in 1876 at the age of 43, an age when Beethoven had already finished eight of his nine symphonies. His Fourth Symphony was completed in 1885. While some view his music as old-fashioned (for late nineteenth century), others celebrate the way he breathed new life into the forms of the Classical period. In the case of the Finale of his Fourth Symphony, he goes even farther back to the Baroque form of the passacaglia. Brahms constructed the entire movement as a set of variations on the opening eight-bar ground yet maintains the momentum of an exciting symphonic finale. One of the ways he achieves his sense of forward movement is by avoiding constant V-I progressions. The first statement ends with an augmented 6th chord, and many statements end on chords other than the tonic.

The overall form of the movement can be described as A B A (with increasingly developmental variations) plus a coda. The flute solo occupies a very prominent place – the beginning of the B section where the meter changes from 34 to 32. While most of the variations in the A section change harmony once a bar, the three bars leading into the 32 section proceed from beat to beat around the circle of fifths, creating a harmonic stretto that sets up the V-I cadence into the B section.

Many things combine to highlight the flute solo variation. Harmonically, all eight bars are accompanied by a pedal E (tonic) in the violas and horns, which seems especially static following those previous three harmonically active bars. (The harmonies do change above the pedal E.) Second, the dynamic level drops to pianissimo during the three measures before the solo begins, and is piano with a poco crescendo during the variation. Third, the texture thins out, with just horns and upper strings in the accompaniment. But the most striking aspect is the meter change that causes the entire B section to function as a slow section within the movement. All these elements draw the listener’s attention to this glorious flute solo.

One of the most important goals in performing this solo is to bring out the overall arc shape of the passage, from the opening piano E to the climax on the high F#, and back down to the final E in the low register. Although the music is marked only poco crescendo, the dramatic impact of the solo will be greater if the peak of the solo is at least forte, as long as the tone quality remains rich and not forced.

It seems to me the key to making this solo musically effective is dynamic control. In addition to having a wide enough dynamic range to build the overall crescendo one must obey Brahms’ <> markings, to make sure that the loudest note of each bar is the 4th note, the peak of each small crescendo. The solo is built on the appoggiatura gesture, so the loudest note of each bar should also be the note with the most vibrato. In a sense there are four appoggiaturas in every bar, but if each of them is shaped equally the listener hears the quarter rather than the half-note beat, and the solo loses its overall shape. To keep each measure moving forward, make sure the second half of the measure (which consists of 5 notes) functions as a pickup into the next bar.

Another key to making the solo coherent is minimizing the eighth-note rests; view the rests as very small spaces that allow you to breathe. Thus, the note after the rest is a continuation of the (same) note before it, so sneak back in without an accent. If you do this, the entire solo seems like one long phrase, reflecting its context of being the 12th variation of the eight-bar ground.

In addition to a rich, Brahmsian tone and great dynamic control, this solo requires impeccable intonation. It is crucial that the Es in each of the three octaves be in tune with the violas and horns (who are hopefully in tune with each other.), so practice this solo with a tuner droning an E.

A second intonation trap to avoid is going flat on the decrescendos into the eighth rests. Finally, make sure the overall pitch doesn’t rise as you crescendo into the high F# or fall as you descend to the low E. Many flutists use the right hand middle finger for the high F#, which helps bring the pitch down.

As flutists we are always looking for ways to develop our sound, and this solo is one of those perfect venues for working on a beautiful, open high register. Because F# is probably not your best note, pick one that is better, perhaps a fifth lower , and practice the figure leading to the high F# transposed down to B minor. Listen to the full and open sound you get on the B; then work your way back up to the E minor version.

There are many wonderful moments for the flute in the orchestral music of the Romantic period, but few are as stunning as the flute solo in the Finale of Brahms’ Symphony #4. There are over 30 variations in the movement, but only one is assigned to a solo instrument. Its placement at the beginning of the slow section in this Allego energico underscores its importance within the piece. By slowing the pace, decreasing the dynamic level, and thinning the texture Brahms uses the solo flute to calm the mood of this intense movement. The solo also ushers in the one section (variations 13-15) in E major. This is a truly remarkable solo, one of our gems from the Romantic era.