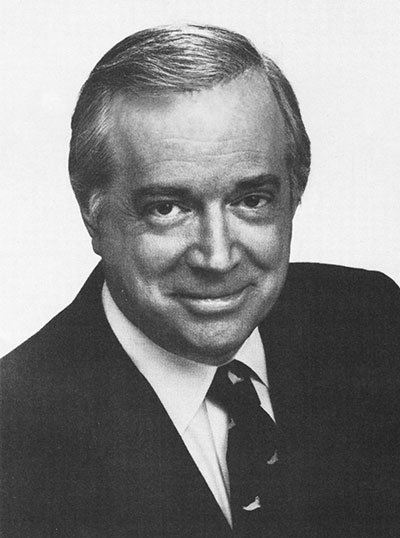

Broadcaster Hugh Downs (February 14, 1921 – July 1, 2020) was in the public eye for more than 50 years, but few people know of his lifelong love of music or his abilities as a composer. The host of the television program 20/20 took violin and piano lessons from age five and wrote a musical setting for a psalm at age 13. After studying orchestration, Downs composed the Elegiac Prelude for Orchestra as well as Sandwriting and several piano pieces, including An Old Familiar Air That Has its Own Tuxedo and Will Travel.

Broadcaster Hugh Downs (February 14, 1921 – July 1, 2020) was in the public eye for more than 50 years, but few people know of his lifelong love of music or his abilities as a composer. The host of the television program 20/20 took violin and piano lessons from age five and wrote a musical setting for a psalm at age 13. After studying orchestration, Downs composed the Elegiac Prelude for Orchestra as well as Sandwriting and several piano pieces, including An Old Familiar Air That Has its Own Tuxedo and Will Travel.

Hugh Downs grew up in Akron, Ohio with a violinist mother and a trumpet-playing father, who introduced him to chamber music. The entire family listened to operatic arias on a Victrola. Today, the internationally known broadcaster is on the board of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and hosts the P.B.S. television series Live From Lincoln Center.

What are your thoughts on the state of classical music in America today?

There are probably more symphony orchestras performing today than ever before. By virtue of the sheer numbers of people, there is also a great deal of musical activity and appreciation for the classics in the United States. However, I worry about it from the standpoint of proportion. For example, composing a symphony now is perhaps not as important or well accepted as writing a film score. In an age of book condensations and life that moves at a hectic pace, it’s difficult to cultivate the atmosphere to appreciate a great symphony.

Though it hardly seems compatible with his character, Anton Bruckner responded to a complaint that his symphonies were too long by saying, "On the contrary, my friend, you are too short." I can understand that, because listening to a Bruckner symphony does take time and is meant for people who have the time to invest in it. It can’t be condensed because it would not survive in that form. To some extent Americans may have lost some of their willingness to invest spiritual and intellectual energy in great music.

I’m saddened by the way many people in this country regard the arts as something nonessential to life. A young boy is taught to deal with the hard realities of the business world and make a living, and if he has the time and the means to buy a slim volume of poetry, well, that’s all right. In America if you ask what someone does, he will describe how he makes a living. In other countries a reply to the same question might be that someone writes poetry or climbs mountains, only later mentioning that he is a bank teller. From this point of view, it is more important who a person is than what he does.

Many countries encourage voluntary support for the arts, which includes official government support. There isn’t much official support in the United States; here arts agencies are under constant attack to cut back their budgets. That kind of philistine thinking bothers me.

Years ago I met a Greek merchant on a plane. At that time I’d never been to Greece and explained how anxious I was to see the ancient glories, such as the Acropolis and the Parthenon. He actually said, "Oh, well that’s all ruined, you know. I have a group of friends who are trying to clear that out to put up some modern buildings." That the treasures of the world are under such pressures is pretty scary.

You’ve met a number of celebrated musicians in your lifetime. Who among them stands out?

Once I shook hands with Sergei Rachmaninoff and was impressed with the size of his hands. I later heard he could play a glissando in tenths. Actually, many musicians I’ve encountered were cello virtuosos. I interviewed Emanuel Feuermann, Gregor Piatigorsky, and Pablo Casals, and more recently I’ve gotten to know Yo-Yo Ma.

Of course, Vladimir Horowitz, whom I interviewed for the Today Show in the 1960s, also comes to mind. He was rather formal and slightly aloof. While I couldn’t call him warm, he was certainly not abrasive. His wife, Wanda, seemed forbidding at first, but became sympathetic as she realized I appreciated her husband’s artistry. As we talked about music he played for me with a powerful touch but with nuance. Had I struck the piano with that much force he probably would have advised me not to abuse it.

I’ve known Isaac Stern for many years. He has always been generous to young musicians and was responsible for saving Carnegie Hall from the wrecker’s ball. While I was laid up in the hospital after hurting my back, he brought me a pair of prism glasses so I could read. It was there that we agreed with a handshake that I would sell him my apartment. Isaac always modestly refers to himself as the world’s second greatest violinist, but refuses to answer any question that suggests the greatest.

I also remember my interview with guitarist Andres Segovia for 20/20 while I was in Madrid for his 94th birthday. The piece was a salute to Segovia, but he died while we were editing it. Instead we wrote the narration in past tense and it became a eulogy. Everyone in the business was curious about how we managed to put it together so quickly.

Is there a reason you keep a low profile as a composer?

Winston Churchill once said about Clement Atlee, "He’s a humble man, and he has a lot to be humble about." In 1946 while working on the Elegiac Prelude for Orchestra, I had no fear about the terrible things the critics might say about my music. Now I’m terrified. I can imagine some critic complaining, "Not bad for an amateur." It withers me just to think about it. The likely reason is that now, having attained some visibility in broadcasting, I would like to be accepted on the same level but as a composer, which will probably never happen.

Describe your earliest attempts at writing music.

Though I sensed my limitations early on, music always intrigued me. I took violin lessons from age five and studied the piano as well. After picking out tunes on the piano, I found ways to vary them, which offered the thrill of creating something different that I could call my own. At age 13, I wrote a musical setting to Psalm 13, which my family’s church organist performed. There’s something about a pipe organ that imposes upon any composition a dignity that it may or may not deserve. That gave me the idea to write something for orchestra, so in lieu of studying composition, I read Forsythe, Prout, and RimskyKorsakov, more or less teaching myself orchestration. I also studied the works of Joseph Schillinger, a Russian-born theorist and composer who advocated a weird, mathematically based system, proposing that certain harmonic progressions were related to spirals. I didn’t want to write slide-scale music, though.

What is the origin of one of your first works, the Elegiac Prelude for Orchestra?

At age 22 I joined N.B.C.’s central division staff in Chicago. With light duties I had frequent stretches of free time as well as empty studios, many with grand pianos. I began writing pieces, and occasionally the N.B.C. Orchestra was kind enough to play them while on standby. The Elegiac Prelude was first performed while the orchestra and some staff members, including myself, were standing by during the 1948 presidential election returns for Truman vs. Dewey. Some years later Skitch Henderson conducted the piece with the St. Louis Symphony, which was still under the direction of Vladimir Golschmann. I heard it only once after that, on the radio the day John Kennedy was assassinated; evidently someone found a tape of it in the N.B.C. library. Given its elegiac nature, it conformed to the somber music the network broadcast throughout that day.

To date other pieces I’ve composed include Sandwriting, which was played by the N.B.C. Orchestra on a late night show, and a few piano pieces, such as An Old Familiar Air That Has its Own Tuxedo and Will Travel. In 1952 I wrote the music to a nuevo-western pop song called The Ride Back from Boot Hill, which was recorded for RC.A. by Gogi Grant. It was on the charts but never went gold or platinum.

Some years ago I spoke on a radio program with Deems Taylor, who called himself America’s most unprolific composer. I told him that as a composer I had him beat, insofar as I was even more unprolific than he. Broadcasting keeps me busy; I need large blocks of time to get something going when I compose.

Who nurtured your appreciation for the arts?

I have vivid memories of my parents playing the violin, trumpet, and piano, as well as listening to a collection of operatic arias on a Victrola. My mother was a fairly good violinist who did some concert work while my father, who introduced my brother and me to chamber music, played tolerably on the trumpet. I can remember listening to chamber music on the radio on Sunday mornings. At first I hated it, in that I associated chamber music with dressing up for church, and yet it planted a seed. Chamber music means a lot to me now.

With regard to your piano music, is the technical level suitable for students?

Yes. That is partly because until I could write beyond my ability to play, I had to play the work at the piano first, then write it down.

What inspired An Old Familiar Air?

In part I was inspired by the amusing title of a piece written by my friend Don Gilles, an N .B.C. producer, called The January February March. While working for the Kukla, Fran and Ollie Show, I met the studio pianist, Caesare Giovannini, who would play the bass part of I Got Rhythm while I played chords – not the melody – in the upper part. It was comical. When he played a tune called The Girls in France, which had somewhat ribald lyrics, I decided it might be fun to write a few variations on it, and An Old Familiar Air was the result.

Who were your most important musical infiuences?

The sincerity of Anton Bruckner’s music inspires me. If Brahms was great in a somewhat aloof way, Bruckner’s greatness reflects a sort of naivete; his soul just pours out of him. Nineteenthcentury music resonates in me; it is so intriguing because of the dichotomy of different musical streams. One links Weber to Beethoven and Brahms while another resulted in Wagner, Bruckner, Mahler, Strauss, and later on Schoenberg, Berg, and perhaps Varese.

How do you relate to late 20th-century music?

I confess to not understanding certain kinds of modern music, but I hesitate to condemn it because I remember a time when all the music composed by Brahms seemed badly astray to me. I thought that Debussy, Ravel, and Stravinsky were completely off the rails, but later came to understand their greatness. So it’s possible I’ll yet grasp Elliott Carter, Wallingford Riegger, and Philip Glass. I have heard things in the world of Krystof Penderecki, John Adams, and Alfred Schnittke that may bring me to a full understanding and appreciation of what they are doing. However, I may never be able to do what they do. Of course, it’s overwhelmingly likely that I also will never be able to do what Bach and Beethoven did.

I was brought up in a strictly classical household, with Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven as the foundation of my family’s musical diet. A friend brought over a recording of Stravinsky’s Firebird, and my parents simply looked at each other in horror as if they were hearing pure noise.

I find that contemporary music tends to fall into two sharply divided categories. One can be profoundly disturbing, such as that of Penderecki, and because it’s so disturbing it may in fact be great; perhaps I’m not hearing it yet. Nevertheless, something about the music grabs my attention, so I think that such works are a serious attempt to codify something aesthetic.

The other category is, for me, simply silly. There may be great intellectual depth, like a finely played chess game, in the music of certain composers, such as Elliott Carter, but I don’t hear what they are doing from an aesthetic standpoint. It’s as if they are attempting to make sure that nothing consonant, harmonic, or sonorous ever happens. When they succeed I often think, "They’ve got to be kidding."

What is the value of the arts in society today?

The bottom line is that the arts are important. I have the feeling that anybody without the ability to appreciate aesthetics is not quite fully alive. Music is so important that I cannot imagine living without it. For me it’s a window to some kind of salvation; whatever there is spiritual in life is most closely approached by great music.

Did you ever consider pursuing a career in music rather than broadcasting?

No. I began broadcasting at age 17 and didn’t have much opportunity for anything else. Music was always a hobby, but certainly there were moments when I thought about it. In my family only my brother became a professional musician; he was a flutist with the Dallas Symphony and once performed in recital with Jean-Pierre Rampal. At times I’d like to turn back the clock and master an instrument, perhaps co study the piano seriously. I’d still love to study conducting.

No. I began broadcasting at age 17 and didn’t have much opportunity for anything else. Music was always a hobby, but certainly there were moments when I thought about it. In my family only my brother became a professional musician; he was a flutist with the Dallas Symphony and once performed in recital with Jean-Pierre Rampal. At times I’d like to turn back the clock and master an instrument, perhaps co study the piano seriously. I’d still love to study conducting.

I understand you are working on a piece for Yo-Yo Ma.

Yo-Yo surprised me on the air during a Live From Lincoln Center broadcast. In the middle of the interview he said, "I understand you’re a composer. If you write something for cello, I’ll play it." When I heard that, my hair stood on end! The piece will likely be called Negantropy, which is a negatively entropic process. In entropy things go from order to chaos – it’s the second law of thermodynamics – but I wanted to start with truly random ideas. The concept of the piece is that something develops out of chaos into a kind of modal sound, and out of that comes the thematic material that evokes 19th century musical romanticism.

You’ve created an impressive body of work on radio and television, but how do you envision your musical legacy?

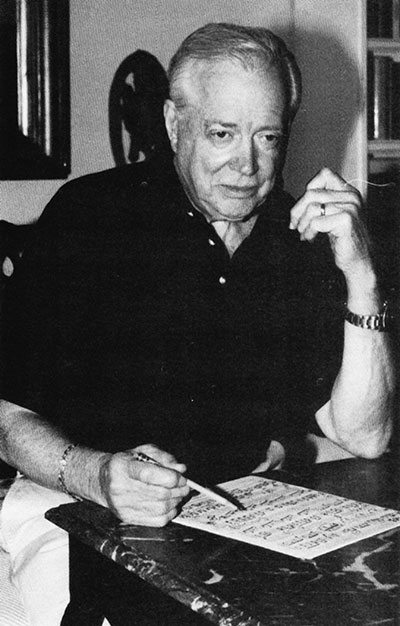

As long as it’s considered for what it is, my music might develop a life of its own within a category of composers who are not known for composing. Even some who were known were professionals in other fields. Borodin, for example, was a chemist, and Rimsky-Korsakov was a Navy man. Your recording brought my attention to the music of Nietzsche, and even actor Lionel Barrymore wrote orchestral music. This is probably the only way I could leave any kind of musical legacy. I can’t imagine that my work will gather a coterie of fans.

If you could step back into the past to meet one of the great composers, what would you ask?

In the film Immortal Beloved, Beethoven, played by Gary Oldman, tried to explain his music to a friend. "When you hear a waltz," he explained, "you dance. When you hear military music, you march. What is it you’re expected to do when you hear a symphony?" He suggested that the listener try to get into the mind of the composer to decide what inspired the music. Something in the labyrinth of great music stuns me with this question: what was so urgent that compelled a composer to write a particular thing? Even if I had the opportunity to converse with a great composer, I doubt he could explain it; but that is what’s so great in music: its urgency, its nobility, and the human ability to hear and understand these qualities.

How would you sum up your musical philosophy?

It’s said that animals have music: birds sing, whales sing. What man calls music is different because we are the only species that pays attention to the mathematical relationships between different tones. I believe the combinations of different rhythms and musical tones resonate within us to create an aesthetic satisfaction. Hearing great music makes us say, "Yes, that’s right." This in tum may relate to the more spiritual aspects of our lives.

I’ve always wondered about the development of polyphonic music. Even in the days of ancient Greece there were strict rules governing the use of modes, and attempts to introduce polyphony didn’t work. It all sounded dissonant at the beginning so man had to develop a matrix for judging it. Imagine the tolerance people had to build. This evolved from a long musical background, going back to the days when man blew in a bone or beat an animal skin to produce sound. Someday I’d love to produce a documentary on the origins of human music. It would be wonderful to put out a set of C.D.s that brings it all together.