When talking with Alexa Still, the first thing that hits you is how unaffected she is. Well, actually, the first thing is her down-under accent, but beyond that you quickly discover what a nice, friendly person she is. While she is one of the world’s finest flutists, highly respected by her peers and much sought after by concert presenters, she is just plain folks – a refreshing, attractive attribute that makes her welcomed by everyone she meets.

When talking with Alexa Still, the first thing that hits you is how unaffected she is. Well, actually, the first thing is her down-under accent, but beyond that you quickly discover what a nice, friendly person she is. While she is one of the world’s finest flutists, highly respected by her peers and much sought after by concert presenters, she is just plain folks – a refreshing, attractive attribute that makes her welcomed by everyone she meets.

Still lives in Sydney today, although she grew up in Christchurch, New Zealand, in a family that enjoyed music and saw it as an important part of daily life. “My dad played saxophone by ear; he can’t read a note of music, but he’s got very good ears. My mom is what you would call a droner. She sings a fourth or fifth below everybody else. She says some people have to be listeners, and that’s how she describes herself. I also have a younger sister who played solo oboe with the Vienna Chamber Orchestra for several years.”

Christchurch has a Saturday morning music school that Alexa attended and describes as fantastic, adding that it has produced many successful New Zealand musicians. “Students really receive a high quality musical experience there. The organization owns instruments that they rent to the students for a small fee. It is a cheap way to get into music, and the organization is big enough to have several youth orchestras. They also offer music theory and history classes. They often hire college students to teach these classes for 6 or 7 students.”

The school also provided recorder teachers for the public schools. “I had a brother who was intellectually handicapped, and my parents wanted me to get into something that I could be proud of – to counterbalance any potential embarrassment – so they sent me off to take recorder lessons when I was four. By the time everyone else learned recorder in school, it was easy for me. I really wanted to play sax and bagpipes, but when I was 8 they got me a flute instead. Actually, I have a set of bagpipes, but I haven’t quite made it past the stage of collapsing into hysterical laughter at the sound I make on them.”

As a teenager, Still began studying music theory with a private teacher. “We didn’t have a piano, which worked out quite well for me because I had to work out the assignments in my head, without the aid of a keyboard. It was quite good training. Then we moved to Auckland, which had youth orchestras. I remember doing Peter and the Wolf when I was about 12 – terribly, I’m sure – but it was good experience. My high school used to loan me to other schools to play Gilbert & Sullivan operas and similar stuff.”

During this period Still studied with several teachers, but describes her first serious flute teacher as “this Quaker, pacifist, Canadian guy named Cyril Haworth. He had studied with William Kincaid and played second flute in the Vancouver, British Columbia orchestra. He moved to New Zealand for five or six years, as an escape from the mechanical drafting work he had done during the war. In New Zealand he taught art in some high schools and flute on the side.

“Haworth was the first teacher who was really picky about my playing. It wasn’t good enough to just play the notes. My mother used to come to my lessons and write down what he said. Those notes are incredible, and I still have them. I studied with him for almost four years, and then he returned to Canada. It was the best flute instruction that I could have hoped for, but he was far beyond where I was at that time. In retrospect, I realize how much I didn’t understand of what he said, and he became tired of saying it by the time I would have understood.”

After high school, Still entered Auckland University, where Haworth was teaching, but he returned to Canada near the beginning of her third year. “I was so stupid when I look back on it. I could have gone somewhere else for my undergraduate degree, but it didn’t occur to me. I finished there in 3½ years, as fast as they would let me. I wanted to get to the northern hemisphere. I went to New York and feel that is where my musical education really began.”

She studied with Sam Baron at State University of New York and with Thomas Nyfenger privately at the same time. “They knew about the dual study and were all right with it. Of course, I never showed up at a lesson and said, ‘Well the other guy said….’ Lessons with them were very complementary because Baron was so passionate about music, and Nyfenger had such amazing technical understanding. I didn’t realize how lucky I was.

“Nyfenger was an amazing player – he could do it all. He had this party trick where he imitated other flutists. He would play in the styles of seven or eight different flutists, back to back, flipping instantly from one to the next. Rampal, Baker, etc. He didn’t have to stop and say who he was playing because it was so clear, and then he would throw your style in the mix. What an amazing capacity.”

Competitions

In 1985 Still won the East and West Artists Competition. The prize was a New York Debut. “I was very concerned that I didn’t let the opportunity go without making sure that everyone who had supported me knew (that took a lot of time) and I played a tough program. I did my unaccompanied pieces, including the Bach A-Minor Partitia, from memory, which was stressful. Everyone knows that if you make a mistake in that one it’s all over.

“I was a broke foreign graduate student. I used to make ends meet by picking cans out of the garbage to recycle for the 5 cents. We worked circuits around the university, collecting cans into big plastic bags. Then we would take them home and sort them by brand before cashing them in.

“I made my dress for the debut, and my husband, also a broke graduate student, drove me into the city from Long Island. Of course we got stuck in horrendous traffic, arriving at Carnegie Recital Hall, as it was called then, about 30 minutes before the concert instead of the hour and a half I had intended. The concert went well, but not the way I had dreamed. I played Bach without mistakes, but I suspect everything in my concert was a little too careful, verging on boring. I received a good review but not the rave I hoped for.

“For my next New York recital I had learned to stay in a hotel for the day so I didn’t have to worry about the traffic. I wore another dress that I had made, but one I had played in before and knew was comfortable. I played a tough program, but I didn’t let myself get stressed or build up unreal expectations. I enjoyed the whole thing that time and got a really great review.”

After her studies in New York, Still returned to New Zealand to play principal in the New Zealand Symphony and soon recorded her first C.D. “The record producer wanted the orchestra to record two discs and decided the second one would be a concerto recording because concertos go together faster than other orchestral repertoire.” Nicholas Braithwaite conducted the New Zealand Chamber Orchestra on that 1994 recording that included the Griffes Poem, Hanson’s Serenade for Flute, Harp and Strings, Op. 35, Elibris (Dawn God of Urardu), Op. 50 by Alan Hovhaness, the Bloch Suite Modale, Night Soliloquy by Kent Kennan, Arthur Foote’s A Night Piece performed with string quartet, and Sir Malcolm Arnold’s Concerto for Flute #1, Op. 45.

However, orchestra life was not quite as rosy as Still had anticipated. “It quickly became clear that orchestral players can stagnate, and some of my colleagues had been there a very long time. It was a slightly scary proposition. I was the first new person in the wind section in almost 50 years. Well – that’s a slight exaggeration, but I was the new kid on the block and the first of a much younger generation. I knew that if I didn’t keep myself busy, I was going to go nuts.”

The Fulbright Grant

She started doing some solo work, and applied for a Fulbright grant to study orchestral excerpts. With a bit of humor and a quizzical smile on her face she explained. “I saw the grant advertised and thought, ‘What can I write that will get me that money?’ I realized that I was playing first flute in an orchestra and had never studied orchestral excerpts with anybody. So I put together the proposal, got the money, and spent two months in the United States taking lessons with about 14 orchestral players. It was fantastic. I can’t describe how much I learned in that short amount of time. I was completely unprepared for those teachers’ diversity of ideas.

“I remember my lesson with Walfrid Kujala well. He spent about three or four hours with me. It was extraordinary. I had prepared questions to ask each teacher, and most of the teachers looked at me as if I was from Mars when I asked them, probably thinking, ‘What an inane, stupid, fundamental thing to ask.’ Wally didn’t even blink an eyelid, and we spent ages talking about stuff. I was so impressed. I played the Leonore Overture for him, and he said, ‘You know – if you didn’t lift your A-finger so high, that passage would be easier.’ I remember thinking at that precise moment, ‘I came all this way, and he’s telling me not to raise a finger too high?’ He was absolutely right – a tiny little thing like that can make a profound change in your playing.”

Touring in New Zealand

Touring in New Zealand

Still returned to New Zealand and continued on in the orchestra for 11 years. “The New Zealand Symphony traveled up to 3½ months out of the year. In a small country with limited performance venues, the orchestra would be booked to perform in a halls and get bumped at the last minute for traveling shows that were coming through the area. I have also done recital tours in New Zealand with up to 19 concerts on one trip. When you play the same thing over and over again, you really learn a lot about yourself, and how to make each performance better. Because some of the places were so small, I realized how powerful music can be. Playing at a relatively remote place for maybe 40 people crowded into a small venue often puts you in the middle of what amounts to a large family. The audience interaction with you and each other shows clearly that they are only there to enjoy some music.

“My favorite memory from those tours is playing in Taihape, in the Taihape Womens Club Rooms, which were set up for farming women, so they would have a place to go for a cup of tea when they came to town to do their weekly shopping. It was a beat up bunch of rooms with walls knocked out, low ceilings, and carpeting. There was a baby grand in the corner that some tuner had tried their best with, and some bailing twine (from bailing hay) held a lamp together over the music stand on the piano.”

Eventually, Still left the orchestra. “The scheduling became a problem. The orchestra received a lot of television exposure, and because I was the home-grown girl and the only female in a principal job (most were foreign players), I was quite literally a balance or bounce spot for the T.V. cameras. I became quite visible in the orchestra, and then the management thought they couldn’t do a concert without me. This was total nonsense, but it was their perception. It got to the point that I would agree to a solo performance outside the orchestra, had written permission to be away, and they would change their mind. That put me in a difficult position, and for that reason I chose to leave.”

Still moved to Boulder, Colorado in 1998, where she was associate professor of flute at the University of Colorado for seven years. “I really liked it there. It’s a great place to live, but my husband, who is an American, really missed New Zealand. The Sydney Conservatory made an offer that included Chair of the Woodwind Area, and it was a no-brainer. The Conservatory draws top students from Australia and the Asian countries, as well as a lot of Americans.”

Sydney is home to the Australian Opera and Ballet Orchestra, the Australian Chamber Orchestra, the Australian Baroque Orchestra, and Sydney Symphony, regarded as the cream of Australian orchestras, but Still has no burning desire play in an orchestra again. “I just try to be a facilitator for flute events and do what I can to use my position to make things happen. I do solos, recitals, and a bit of chamber music with some of my university colleagues, but I try not to step on the freelance players’ toes.”

On Asthma

Although you would never know it from hearing her play, Still is asthmatic and has been since about age seven. “New Zealand has one of the highest instances of asthma in the world. There are all sorts of theories about why, and one of them is that the majority of New Zealand is technically a cold rain forest. It is so moist that lots of molds flourish. Another theory is that asthma is triggered by certain foods. Because of this, I have to be a bit more aware of what I eat when I perform. When I get a cold, it often lasts a long time and goes deep in my lungs. I have learned the hard way that I have to stay fit, so I swim. The one benefit to asthma is that you become aware of your body and what your breathing is like. You know whether you are having a good or bad day. I think most people aren’t very aware of how they breathe.”

Teaching

“I’ve always thought my teaching was a bit unorthodox, which is why I’m a bit scared to publish a pedagogy book. On the other hand, I think flutists are a lot more open to opposing ideas about their instrument than other wind players. I’ll be more comfortable when it is easier to incorporate sound and images into the publishing. One of the attractive things about teaching at the conservatory is that it leans toward the European teaching model. Students receive an hour a week with me, but I also coach an excerpt class, a flute class, and a woodwind masterclass, and I only have 13 students.

“Over time I have arrived at what might be judged unusual pedagogy. When a student has technical problems, I prefer to design or adapt exercises for that particular student and situation. I’m a great fan of working by ear, as opposed to being glued to written music. I often include ways to do things that seem impractical, where I think the work is extremely valuable in developing other essential listening skills or flexibility. Conversely, when I can’t find an important justification for the usual methods, I often skip over standard steps that just don’t seem that useful in a real context. I like using tools such as mirrors, computer cameras, strapping tape, and even ear plugs.

“I encourage students to listen to other musicians and get accustomed to working from scores rather than just flute parts. This is something Thomas Nyfenger insisted upon, and I think it makes very good sense. In the beginning, I suggest various listening possibilities, which I hope will make them think and realize that there isn’t just one right way to interpret a piece of music. I ask students many questions. We eventually spend a lot of time experimenting with various ideas on a portion of the piece, and then I leave them to figure out the rest. I want them to learn how to be convincing and how to do this for themselves.

“My interest in ergonomic adaptions for the flute comes from a former student, Megan Glass, who had remarkably fast fingers yet still had difficulties with a section in the Carmen Fantasy. I remember being somewhat frustrated and thinking to myself; ‘Why the heck can’t she do that?’ After trying it myself, which didn’t help, I began to be extremely observant as she tried the passage again. It was a light bulb moment for me, watching someone else’s hands in action, and the beginning of a journey in understanding.

“Later that year, we designed a key cluster for her foot joint , which was done by John Lunn. It made a profound difference for her very short fingers. I think it is relatively easy to teach one’s own challenges, but ergonomic challenges just don’t occur in my playing because my hands are freakishly massive. My family has always teased me for having fingers like E.T. However, I seem to have developed a bit of a reputation as a teacher for being constructive and dealing effectively with technical problems related to position, and I owe Megan a big thank you for the gratification I feel in helping players who are having similar problems.”

Advice for Students

“Today more than ever it is important to be your own person. Players are more and more competent, but it makes it even harder to do something individual. The pressure to play faster, in tune, etc. sometimes comes at the expense of players’ individuality. When I think about all of the successful musicians I know, there’s something very distinctive about each of them. None are what I would describe as a generic player. Students have to figure out who they are and know that things change over time.

In days past, teaching was more along the lines of, ‘This is how I do it. This is what you will do.’ or ‘Copy my Bach markings. They came from Kincaid.’ Now you have to think for yourself. Perhaps I was lucky that none of my early teachers played the flute for me. The first time I had a teacher with a flute in the room was when I studied with Thomas Nyfenger. Also, at that time there were fewer recordings available.”

Practice

I try to practice a couple hours a day. When I am working on a program or learning new repertoire, I probably practice about four hours a day. How you approach practice mentally is important. We can be very inefficient, and I would include myself in this. When I’m really practicing well and thinking properly about what I am doing, I don’t practice that much. When I am properly focused, I do spectacularly good work. It is amazing what I can get done in a very short amount of time. That sort of practice is extremely intense and carries over well into a performance. My goal is to have the same intensity of attention and mental imagery during practice as it will be in a performance, so there is simply not much difference.”

A Passion for Motorcycles

A Passion for Motorcycles

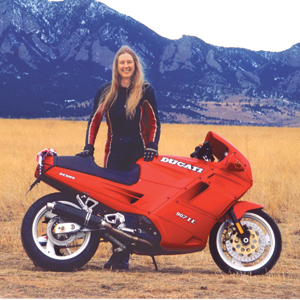

In addition to her love of music, Still is a motorcycle enthusiast. “I love my bike. When I was a poor student in New York, I couldn’t afford car insurance, and the public transport system around S.U.N.Y. Stony Brook, where I went to school, was pathetic. I began riding on an old 1976 Honda 550. It had four in-line carburetors, and I was forever pulling off to the side of the road and burning my fingers while urgently unscrewing the carburetor bowl to clear some piece of gasket cement from the needle in the carb. My husband taught me to do the timing and adjust the valves. Eventually I got a Ducati after hearing one in a bike shop. Ducatis are Italian, handle nicely, and sound unbelievable. They also pass muster with Harley drivers because they are so cool.

“I’m on my second Ducati now, a Paso 907ie. People are always complimenting me on my bike. I’ve even had some lucky breaks with minor traffic offenses, largely because the cops were surprised to find me beneath the leathers, sun glasses, and helmet. The best thing about riding a bike, however, is meeting a different segment of society. I like having contact with what I describe as ordinary people. When I chat with a biker, music doesn’t even enter the discussion. I appreciate being just another person.” Still says, “I think the addiction to motorcycling is that it feels as if you are part of the scenery, more involved and exhilarated than the feeling you get from being isolated inside a car.”

What the Future Holds

Still has released 14 recordings, most of which are with Koch. “I have another C.D. in the can that hasn’t been edited yet. It includes Schoenfield’s Slovakian Children’s Songs and the Irving Glick Sonata, (a Jewish Canadian who died in the 1980s). The Glick has been out of print for a long time, and it took a while to even locate a copy of the score. The music is in the middle of an estate battle, which explains its unavailability. It’s a beautiful piece that should be well-known.

“I am also working on a research project on flute pad surfaces. Flute making has come such a long way, but flutists today mostly still use gut skins for pad surfaces. There has to be a better way.

“I enjoy playing music that belongs in the cross-over genre, and I am currently working up a program of unaccompanied music like that. I have done unaccompanied recitals for years, but some pieces are more successful than others. Putting an entire concert together of music that is equally powerful and diverse enough to hold someone’s interest is a challenge. Someday I would like to play a concert that interests flutists, classical musicians, and people who don’t know much about music at all. I think it’s possible, but a demanding task.