In order to play well in orchestra or chamber music, you must understand your role and be willing to yield the spotlight to other players. Sometimes roles are straightforward and well-defined. For example, your colleague has the melody, and you are accompanying, perhaps with sustained chords under the tune. Or your part moves with the melody, maybe in thirds or sixths, but is still the harmony part. Often in an orchestral flute section, the second or third flute “ghost” the principal – they play the same notes and rhythms with the intention of sounding like one large flute. Be aware that vibrato can interfere with this effect.

Flute and oboe frequently play in octaves to create a special blend, and flutists should be careful not to stand out too much from the oboe’s sound, as this can create a shrill imbalance. Vibrato should be eliminated entirely or at least kept to a minimum by both players, and subtle changes to the printed dynamics may be in order depending on the context. All of these instances require careful listening and tonal flexibility in order to blend or emerge.

Many times, players switch roles in the middle of a passage, with one suddenly emerging above the other voices, using a soloistic approach, or conversely, disappearing into the background with a diffuse sound and no vibrato.

All of the above can be quite difficult to accomplish without skewing the intonation or distorting attack and articulation.

Trading Roles

There is an additional, common chamber music configuration in which the challenges may be still greater: the rapidly trading central role. More complex, polyphonic and imitative writing frequently takes this guise. Skill with quickly and lightly shading the tone is required to effectively address this type of writing. The purpose is to clarify the texture so that the listener’s ear is always drawn to the most important material. If handled too casually, the voices in complex writing can sound like a nursery school classroom with each child clamoring for attention.

Many Shades

Though yielding to the other voice (shading) is a commonly practiced and rather rudimentary chamber music technique, rapid exchange of emphasis between voices, which can occur in various ways, is not so simple. Each passage has its own identity within the style and character, and shading should be applied appropriately, sometimes with great subtlety. Developing facility takes a bit of practice. Luckily, it is fun. Ask a colleague to join you in the following simple examples from the duet in E-flat major by Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (1710-1784). (Note: in my International Music Co. edition, this duet is in Volume 1, No. 3).

Basic

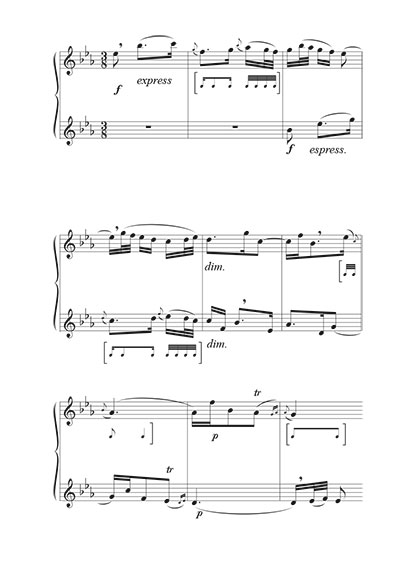

Mvt. 2, Adagio ma con molto, mm. 17-23

This passage illustrates the basic technique. Players should attempt to match tone quality and vibrato, and tune carefully. In measures 18, 20, and 22, Flute 1 naturally makes a small diminuendo into beat 3, as dictated by the harmony (it is the resolution). This shading allows Flute 2 to have the solo in those measures. Vibrato on beat 3 should be minimal or excluded, and players should take care to avoid sagging pitch. Flute 2 shades in measures 19 and 21. Shading means playing a bit softer without actually changing the dynamic in most cases. Here it should be accomplished within a forte dynamic.

Faster

Mvt. 2, Adagio ma con molto, mm. 29-37

This passage (shown at the top of the next column) from the same movement illustrates how shading technique is used according to the length, construction, and harmonic rhythm of the phrases. In measures 29-30, Flute 1 has the melody alone. In measures 31-32, Flute 2 has the primary voice, while Flute 1 is the accompaniment – but notice that the accompaniment is a moving voice. Generally, within the bar, moving notes should always briefly emerge in either voice. Flute 2 can slightly shade the dotted eighths in the melody in order for this to happen. If they are played too sostenuto, the moving line in Flute 1 will be obscured. In measures 33-34, harmonic rhythm is faster, and voices trade more rapidly. The player with the dotted eighth should shade slightly to allow the other moving voice to be heard. This can be done by placing a tiny diminuendo after the attack of the note. You can create a space on the dotted eighth, but the phrase might sound stilted. Long notes in measures 35-36 can be de-emphasized through a softer dynamic within the diminuendo. Vibrato should be kept in check by both players throughout the passage, as it tends to cloud the texture and draw attention to itself.

Harmony Too

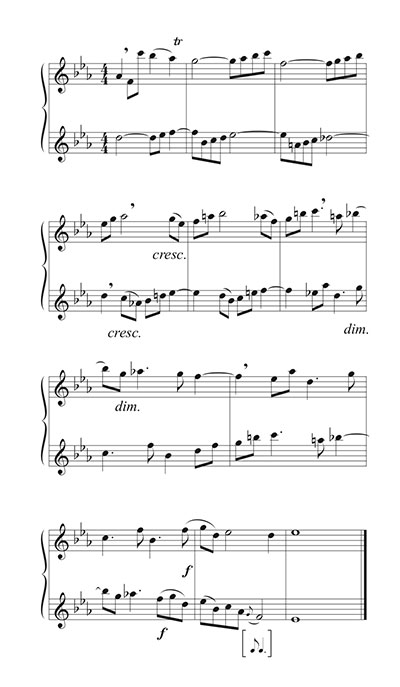

Mvt. 1, Allegro, mm. 98-108

Practice changing the rate of trading the spotlight in this passage. In measures 103-106, the rate of trading doubles with the voices alternating within each measure. Very subtle shading should occur on each dotted quarter note. In meastures 99-102 there is an interesting detail where harmony comes into play at times. Like moving notes, dissonances should generally be highlighted in the texture, as they represent a higher state of drama than consonant harmonies.

Each measure in this segment contains the dissonance of a second on the downbeat in the form of a chain of suspensions. If players exaggerate shading on the half notes and neglect to sustain into the tied notes, they are at risk of ignoring the dissonances. The half notes should be shaded very delicately, and perhaps a tiny crescendo applied at the moment the tie occurs, reinforcing the suspension. To complicate matters, this descending sequence should probably receive a slight overall diminuendo, which is not only appropriate to the style, but prepares the approaching crescendo in measures 101-104.

Balance

Mvt. 2, Adagio ma con molto, mm. 49-57

Shading is always relative to the register in which one is playing. The higher the note, the louder it is. In a manner very similar to the last example, measure 49 begins with the melody in Flute 2, who is then accompagnato in measure 51, where care must be taken regarding registers in order to balance. It is very easy for Flute 2 to be too loud. Exaggerate the piano dynamic. In measure 53 Flute 2 again has the principal voice, and Flute 1 should now alter the dynamic a bit towards forte in order to be heard playing the accompanying moving line a tenth lower, as low register notes are generally softer. In measure 55 the opposite occurs with Flute 2 having to shade for Flute 1 to emerge.

Character and Direction

Mvt. 3, Presto, mm. 7-11)

Just as register affects shading, so do direction of line (rising or falling) and character (technical writing vs. lyrical). In this fugal example, Flute 2 has the counter-melody in measures 7-9. Care should be taken with the 16th-note passage in measure 8 so that the virtuosity does not overwhelm the theme in Flute 1 in the low register. As the voices are crossing, balance can take care of itself; Flute 1 will become more present, and Flute 2 should weaken a bit in the descending scale and arpeggios in measure 9. Flute 2 should be aware that the last note of the flourish in measure 10 should be more present. It seems like the downbeat should be a normal unaccented resolution, but it should be immediately brought to the forefront as it is the first note of the next thematic statement.

Mvt. 3, Presto, mm. 22-24 & mm. 62-64

In both of these examples (shown below), care should be taken by Flute 1 to not overpower the theme in Flute 2 which is in the low register. In a contrast to the natural tendency, the accompanying ascending scale should have great energy but also a slight diminuendo to remain in balance.

mm. 22-24

mm. 62-64

Care and Share

With determined practice these subtle balancing tricks become second nature. Once basic habits are mastered, more artistic concerns can emerge. Global aspects of general and specific phrase shape, mood, clarity of the composer’s message, and the pure joy of sharing chamber music with colleagues can receive the attention they deserve.