When I first started teaching, I assigned etudes with little explanation assuming that what the exercise was about would be obvious to the student. I made a realization that this was not true when a student commented, “I wish I had known what this exercise was about before I started my practice week.” From then on, I started talking about the etude’s purpose and offered practice suggestions for success.

Carl Joachim Andersen (1847-1909) was a Danish flutist, composer, and conductor. Both he and his younger brother Viggo learned flute playing from their father. As a young man Joachim played principal flute in the orchestra in Copenhagen before moving on to the Royal Danish Orchestra and the St. Petersburg Philharmonic. In 1882 he was a cofounder of the Berlin Philharmonic and solo flutist with the Royal German Opera. Unfortunately, he developed focal dystonia in his tongue so he was unable to continuing playing. Instead he returned to Copenhagen in 1893 where he founded an orchestra school. In 1905 he was knighted by King Christian IX of Denmark to the Order of the Dannebrog.

Andersen was a prolific composer for flute. He composed a variety of solo works plus many etudes for flutists of all levels of proficiency. His opuses or opera ranged from Op. 21, 37, and 41 for school-aged flutists to Op. 33, 30, 63, 15, and 60 for college/conservatory students and professional flutists. Most professional flutists regularly revisit these etudes because they focus on the technical aspects of playing the flute.

In the Flute Talk November 2014 issue, John Barcellona shared the teachings of his mentor Harold Bennett on Andersen’s Op. 33. The next opus in difficulty is Op. 30. These are my ideas in a study guide form. Opus 30 is published separately, may be found in the Big Blue Book or Famous Flute Studies and Duets published by Southern Music (now Hal Leonard), or downloaded for free from www.imslp.org.

As in most of Andersen’s etudes, Op. 30 (written in 1888) begins in the key of C major followed by the relative A minor and proceeds clockwise around the circle of fifths. There are 24 etudes in the set, one for each major and minor key. When I ask students what Andersen was doing in his writing of these etudes, most will say that the goal is to teach flutists to play in all the keys equally well. This is a start but is only part of the story.

When teaching Op. 30 to less experienced players, start with etudes 1-14 and then proceed from the end of the book backwards starting with 24. For some students this makes a more logical approach rather than going around the hump of the circle of fifths.

In the first edition (and in most that have followed), there are tempo markings for each etude. Generally, these markings are too fast. The metronomes of Andersen’s time were of the windup variety, and the ticks per minute varied greatly from one metronome to the next. There is an old adage from Richard Wagner’s conductor friend Hans von Bulow that flutists would do well to remember. There is always one place in the music that will tell you the tempo of the piece. Usually this is the measure with the most notes to play.

As with any new music, having control of major and minor scales, scales in thirds and sixths, arpeggios, and seventh chords will make learning it easier. At least a third of each day’s practice should be spent on perfecting the theoretical fundamentals, and then next third on etudes and the final portion on repertoire and excerpts.

If there are difficulties with playing the notes, practice some repetitions. Play each note four times, then three times, then two times using T, K, Hah, or TK. Practice rotating back and forth several times between difficult note connections. Play slowly at first for accuracy. Chunk by beamed notes, by slurs, and then by two and four bars. Practice tonguing the entire exercise using T, K, or Hah syllables. Practice in dotted rhythms (long, short and short, long) too.

No. 1, C major

This etude is based on a two-measure motive and focuses on playing ties. The idea is repeated many times throughout the etude. Most conductors suggest not playing the tie, but getting off of the tied note early in order to be in time for the following notes. Use the phrasing rule DDT or decay to the dot or tie to enhance musical interest. This means getting softer over the first two beats of the first measure. The sixteenth notes should be grouped 2341. Chunk the sixteenth notes in the 2341 group several times to develop flow. Since the phrase is going to 1, which should be the strongest note, begin softly on the 2 making an increase in volume until reaching 1.

In measure 32 (or in some editions, the second measure after the repeat, Andersen wrote a slur from a third-octave A to a third-octave E. With the regular fingering there will be a wolf or cracking sound between the A and the E. Removing the right-hand pinkie for the E and then quickly replacing it will solve this issue. If you have a split E mechanism on your flute, there will be no problem. When Andersen wrote these etudes, the split E was not common.

Beginning in measure 49 and in several other places, there are wide intervals that are more difficult to produce. Make the aperture smaller so the high notes can be played mf. Joseph Mariano, legendary flute professor at the Eastman School of Music, said, “Never leave an exercise un-tongued.” He explained that there were so few all-tongued exercises that flutists should tongue every etude at least once to practice articulation. When tonguing, fill in the notes of longer note value with sixteenth notes. Repeat using the T, K, Hah, and TK syllables. Do notice the word cantabile in the first measure.

No. 2, A minor

This etude should be played in one, remembering that the first beat of the measure is the strongest. Phrase in eight-bar measures, breathing after one in bars 9, 17, 25, etc. Andersen wrote con grazia (with grace or gracefully) in the first measure. When I studied these with William Kincaid, legendary flute professor and principal flute of the Philadelphia Orchestra, he wrote several grouping patterns at the top of the etude and suggested I try each to figure out which one worked best for each measure. Here are his grouping patterns or think marks:

1, 234561 (see m. 2, 3, 4, 7, 8)

1, 23, 4561 (see m. 2, 3, 4, 7, 8)

1, 2345, 61 (see m. 5)

Chunking each pattern will help determine which works best for you. Rather than making a crescendo/diminuendo with the hairpins, try thinking of them as energy marks as there will be a natural increase in dynamic as the notes ascend and a decay as the notes descend. Place a mordent of vibrato on the first note of a slur. This is difficult to maintain throughout, but will make you sound more like a pro and less like a student.

No. 3, G major

Kincaid said this was an etude to practice playing first notes. He suggested shortening the eighth notes to sixteenths and placing a sixteenth rest between each note to create a definite articulatory silence. Single tongue each note with the tongue pulling back from the top lip or the hole in the aperture. It is difficult to maintain this articulated style throughout, but try because this will improve the quality of the attacks in everything you play.

In measure 12 the third note is a B rather than the printed D. This exercise is also about the right-hand pinkie. There will be a tendency to not put it down on notes following low D. Circle in red the notes following the Ds to remind you to use the correct fingering. The note groupings are very interesting. In measure one the grouping is 1, 23, 45, 67, 1. This produces a compound melody between an upper and lower voice. In measure two the grouping changes to 12, 34, 5, 67, 81. The middle section of this etudes is in G minor, the parallel minor key to G major. Notice the quick changes in dynamics and the accents over certain notes. Sometimes it is easier to make the non-accented notes softer rather than making the accented notes louder. This offers more control. Another way to practice this etude is to place two or three notes per each written eighth note. Use double or triple tonguing when practicing this.

No. 4, E minor

This etude is about playing softly and easily. The tongued notes are the melody, and the slurred notes are the accompaniment. Play the etude once through playing only the tongued notes and omitting the slurred ones to hear the melody. In the first measure group 1, 23, 4, 56, 789101112. In measure two group 1, 23 throughout. In measure eight, the slur is misplaced on the first beat and should be played tongue one and slur two. As you progress through the etude, it is easy to start to play louder. Circle in red all the pp as a reminder to pull back the dynamic.

No. 5, D major

This exercise is about the right-hand pinkie. For notes following a middle or low D, the right-hand pinkie should be down. Play very slowly concentrating on using the correct fingering. The motive or pattern for this exercise is two bars in length. It will be the first bar of each pattern where playing the correct fingering is critical. Play this etude through, playing only the odd numbered measures. This measure features two-note slurs. When playing these slurs, the second note is a resolution and should be played softer than the first. Repeat playing the even numbered measures playing the sixteenth notes as one gesture, and not making smaller groupings. Every two or four bars Andersen changed the dynamic. As an orchestral player he knew how important it was to respect the dynamics.

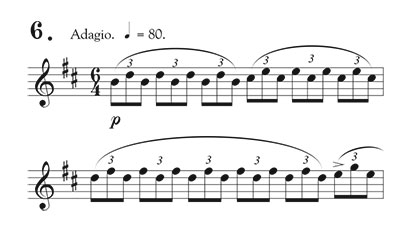

No. 6, B minor

Written in 6/4, this etude should eventually be played in two which is a challenge. Andersen was still concentrating on the use of the right-hand pinkie which is a good follow up to No. 5. This etude is also about balancing the flute in the hands. The first note is fingered in the upper stack and the second note in the lower stack. The tendency is to let the flute move from a balance point to the left then to the right when what you want is for the flute to be balanced and still with only the fingers moving. Set the aperture for the upper note as it will be easier to play smoothly.

This exercise is easier to play at p rather than a louder dynamic. Notice the accents. Rather than playing them louder, try coloring the note with a smidge of vibrato to bring out the melody and play the non-accented notes softer. Practice by chunking by the quarter note – playing a certain number of notes on one blow of air followed by a rest, and taking a sip breath in each rest. Then chunk by slurred groups of notes. Andersen used the dynamic of pp a lot in this etude. Maybe the flutists of his time played too loudly much of the time too.

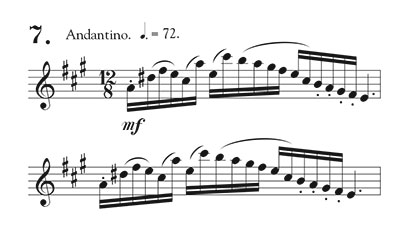

No. 7, A major

This etude is about playing in two measure phrases with varying articulation patterns. Each time you finish one slur and begin the next, place an articulatory silence between the groups. Otherwise it will sound like one long slur. For intervallic skips of a fourth or more, slightly lengthen the note before the slur (but still being in time) to make the skips sound easier. You may change your lips on the notes before the skip in preparation for higher notes. Kincaid changed the tempo marking for this one from dotted quarter = 72 to 60. It is more difficult to play at a slower tempo.

No. 8, F# minor

This etude asks the question about pickups. Do you want to play these in time or slightly slower? Kincaid suggested using the following tonguing pattern for the opening: TT, TKT etc. Mariano started with KT, TKT. The Mariano approach works well with the repetitions throughout the etude. Since the K stroke is always weaker than the T, practice the entire etude with the K trying to make it the same as the T. If you can go fast enough, breathe after eight measures. Notice the p dynamic is used throughout with a few exceptions.

No. 9, E major

While this Lento etude is marked half note = 50, practice by subdividing and playing in six at 100. I was taught to play the pickup grace notes before the beat, but after learning more about early music practice, I also practice playing these on the beat. The first problem in rhythmic accuracy occurs at the end of beat one. Where do you place the sixteenth note B? It should be on the fourth part of the second beat when counting in 6. This pickup recurs throughout and offers many opportunities to be accurate. There will be a slight separation between the pickup note and the third beat because it is best to separate repeated pitches for clarity. If you have a C# trill key, use it on the opening B to C# trill. If not, trill the left index finger and left thumb. Moving these two keys at the same time is something to practice in the mirror to be sure they are synchronized. Usually the thumb is the problem and moves slightly slower. On notes of longer value that are tied, follow the DDT rule (decay to the dot or tie). Release the end of the note with elegance. Carefully check each trill to be sure you are trilling to the correct pitch.

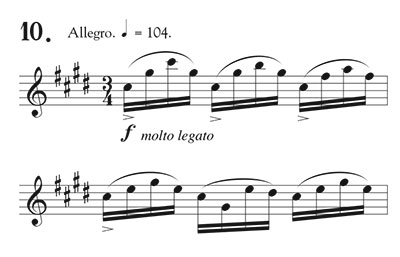

No. 10, C# minor

This etude is in da capo form. For the B section, Kincaid added poco piu mosso which means that it is played slightly faster. The opening features a pedal C# for two measures, then a pedal B# for one, returning to the C#. This C# is a sharp and hollow note, so experiment with alternate fingerings for it. Each flute is different in its response, so you may need to try several options. For the B section, double tongue lightly. Notice the sudden change in dynamics occasionally from p to f. Work to keep all these double-tongued notes homogeneous in sound.

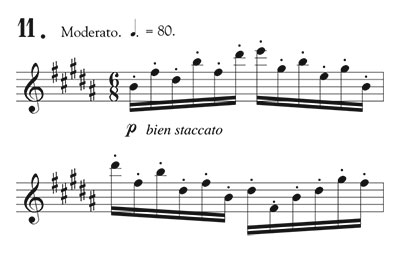

No. 11, B major

This etude is staccato throughout. Staccato means the notes are detached not just short. Practice first with the Hah syllable. The Hah or throat staccato is done in the focal folds, so there should be no movement in the chest or abdomen. If you have movement, try playing softer. Once you have conquered Hah, keep breathing the same way only add T and K. This will give each note vibrancy. The grouping pattern 1, 23, 4561 works well, but you may want to try the others listed for No. 2. If you are thinking of this etude as a dance, breathe on the bar line. If not, then breathe after the first sixteenth every four bars. I prefer breathing on the bar line so the first note is the main importance, and the others come away from the beat.

No. 12, G# minor

Rhythmic accuracy is a must for this etude. The beginning section is preparation for the section in E major that employs mordents. The rhythm is short, short, long which is a slower version of a mordent. Each slur should have articulatory silence before the next slurred group of notes. Notice that Andersen wrote con energico (strong, with energy) and be sure that the accidentals are carried throughout the measure. Slow chunking by beat will ensure success. The middle section con gusto is a study on placing mordents on the beat. Kincaid had me play this section for several lessons to be sure that I had control of the rhythmic placement of the first note of the mordent and that I played them in a short, short, long pattern rather than as a triplet. Check the fingerings for the mordents. C# to D# in the middle octave uses both trill keys.

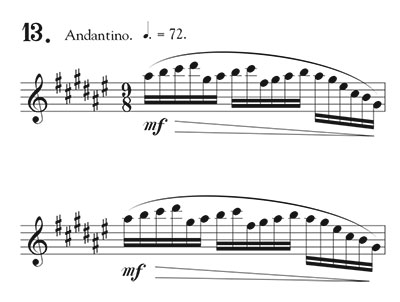

No. 13, F# major

The notes in the opening are stepwise by fours; however, the beat is by the six beamed notes. Practice with the metronome to be sure that there are only three beats in the first measure. Breathe by four measures until measure 22. Breathe in the bar line after measure 22, after beat one in measure 25, after beat two in measure 26, after beat one in 27, after the C# in measure 29 and the finally after the C# in 31. Play very smoothly with a good legato following the tapers are the end of most measures. Color vibrato on the first note of the slur will add finish to the performance. For the final F#, use the middle F# for better intonation.

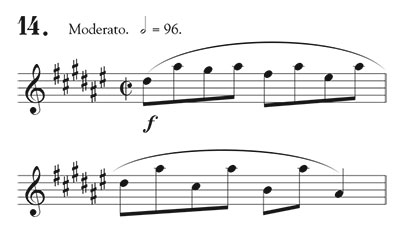

No. 14, D# minor

This etude is for embouchure flexibility. For success, either change the angle of the air, change the size of the aperture, or increase the speed of the air. There are places for each suggestion throughout the etude. The notes that come on the beat are more important than the notes that come on the and. Playing in two, feel more of an up and down motion like riding on a merry-go-round. For the F# in the top octave, the note may speak better using the middle F# fingering. Dynamics continue to be important in this etude.

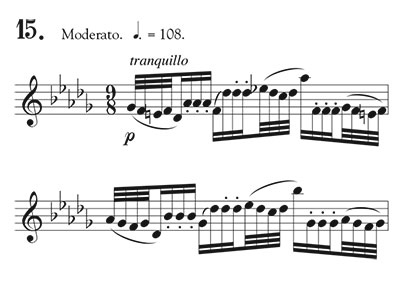

No. 15, Db major

Play in a slow three. All notes spring lightly from the first note. In the last measure before the middle section the 13th note in the bar is a G natural. In the fourth bar of the middle section, the first beat could have been written more clearly. Basically, it is six sixteenth notes slurred by threes. This idea is repeated in bar 7. This section is marked dolce so play sweetly.

No. 16, Bb minor

While this exercise is written in two, better accuracy is obtained by playing in a subdivided four. The problem that Andersen is presenting is how to handle the trill when it begins on the upper note. Since these grace notes have a slash through them, they are played before the beat but as close to the beat as possible. Practice to treat each grace note the same throughout the exercise. Michel Debost has mentioned that when the French begin a trill, they hold the first note for a nanosecond to establish pitch before trilling. This idea works well here and will give the music a more finished sound. All trills throughout should be the same speed. Some trills are more difficult than others and will take practice to control them.

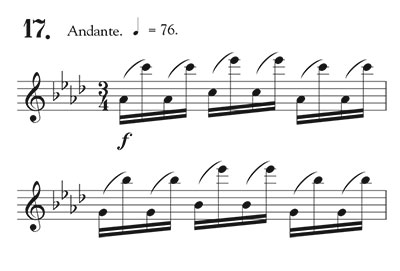

No. 17, Ab major

This exercise focuses on playing ascending and descending 10ths. The two-note slurs should still be played strong/weak or loud/soft which offers a huge challenge with the high notes. Start practice slowly and then speed up. To execute the tenth, you should either change the angle of the air, change the size of the aperture, or increase the speed of the air.

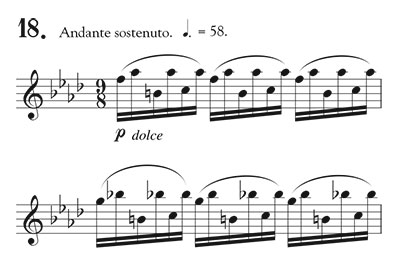

No. 18, F minor

Played in two- or four-bar phrases throughout, this exercise is about repetition. Each first beat is repeated two more times to fill the measure. So, before practicing the exercise all in a row, practice only the first beat of each measure until you can play each one well. The strongest note is the first note of the six. Group the motive 123456 with 1 being the strongest note. This is a great exercise to play with the Hah attack to find the exact placement of the aperture and jaw for ease in playing. The opening is marked dolce and the dynamic is p most of the time.

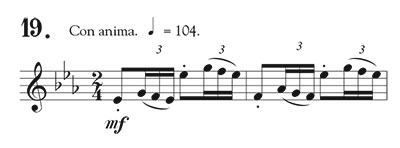

No. 19, Eb major

The A section of this da capo etude features notes of shorter value (triplet sixteenths) leading to notes of longer value (eighths). The eighth notes all have staccatos which in this case means to play them at half value. The pickup triplets should be softer than the eighth notes. Each fourth bar of the phrase is straight sixteenth notes that should be played as one group on one blow of air. While the first ending is a repeat ending, the second first ending leads directly into the B section. It is labeled un poco piu mosso (a little faster) and should be played in long phrases double tongued. In bar 18, the second note is an A natural. Practice breathing at the beginning of the B section, then again after the first sixteenth in bar eight, and then after beat two in bar 16. Repeat this structure in the next sixteen bars.

No. 20, C minor

First, play through this exercise without any grace notes to learn the structure of the melody. The exercise is in three with a triplet on each beat (long, short). This type of grace note with the slash is called an acciaccatura. It is played as close to the principal note as possible and begins before the beat. These intervals are wide so when encountering one that is difficult, practice those two notes slowly until you are proficient. Follow the dynamics carefully and think of the hairpins as energy marks.

No. 21, Bb major

This is an exercise of octaves. Before you begin to work on it, go through and place an asterisk above any two notes where the fingering changes. In the first measure this will be the D, G, and F. Octaves are not difficult to play if no fingers move; however, changing fingers creates coordination issues. Practice the octaves where the fingering changes until you are proficient with the interval. Seeing the asterisk above the pair of notes with the changing fingers will alert you so you will execute the interval well. Two-note slurs are played strong/weak or loud/soft. This is also a good exercise to double tongue. For variety, place two notes (TK) on the lower note and one on the top note. Then reverse for a challenging tonguing workout.

No. 22, G minor

This triple tonguing exercise features a secret melody. It is your job to bring it out. The melody is the first and the third note of each triplet. The second note is the accompaniment and should be played softer. Andersen labelled this con fuoco (with fire) with a staccato on each note throughout. Remember this is in 3/8 so the eighth note will receive one count in measures with two triplets. Notice the dynamic is p at the beginning and there is a crescendo for four measures. Andersen carefully labelled each phrase with a dynamic design. Be sure your listener (or teacher) can hear his plan.

No. 23, F major

.jpg)

The grace notes in the opening are played before the beat. You can tell this because of where he places them in the measure. Unlike No. 8, Andersen has placed the grace notes before the measure much like a pickup. The opening is based on three eight-bar phrases. The next section is an ornamented version of these three phrases. Sometimes I have students play the opening without grace notes while I play twenty-four measures starting in measure 25. Then we switch parts. The is one of the loveliest etudes in the collection. Play with a beautiful, singing, ringing sound following the dynamics.

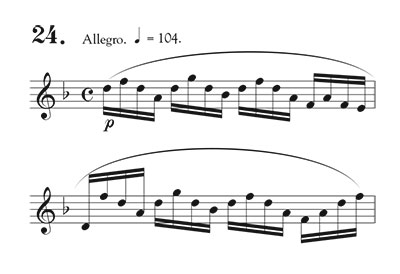

No. 24, D minor

This last exercise features a rhythmic play on four sixteenth notes. First, they are played evenly, then in the middle section the last three sixteenths become a triplet. Be sure a listener can tell the difference. Rather than playing this in four, try playing in two so that there is a better line. Notice the p dynamic again. Andersen was an excellent musician and knew that the best players follow the dynamics to extremes. This exercise works well tongued, double-tongued, and then triple tonguing the triplets.

If you are just learning to play the flute, and this is your first time through these etudes, study one in depth for a week and then move on to the next. These etudes are so good for the advanced flutist that most put them in an etude rotation and play them throughout their lives. I first learned them as a teenager, but have cycled through them for years. Each time I find new challenges and musical ideas that I want to do with them both technically and with my sound.