With the increase of flute choirs, more flutists are trying their hand at composing and arranging for the ensemble. Many begin by writing for a group in which they perform.

Getting Started

For your first arrangement, start with a piece of music in the public domain that you think would sound good arranged for flute choir. Consider starting with a simple four-part vocal arrangement for soprano, alto, tenor, and bass from a hymnal, or another four-part choral piece.

The simplest arrangement is to transcribe the soprano line for flute 1, alto line for flute 2, tenor line for alto flute, and bass line for bass flute. Create the score on staff paper or with a notation program. Arrangements in block scoring are good for less experienced players and arrangers. Independent parts work well for more advanced players. Transcribe the music so that the parts are easily played. Do not create problems with unique scoring. Consider the following as you create your score:

• In choral music, the tenor voice part, usually written in treble clef, sounds an octave lower than written.

• Alto flute is a transposing instrument in the key of G, sounding a perfect fourth lower. During the arranging process, the alto flute part may be written in concert pitch in the score, but remember to transpose the part before it is given to an alto flutist. Once you are sure that the notes of the arrangement are correct, transpose the alto flute part up a perfect fourth, and add one flat to the key signature (or remove one sharp) on the alto flute part. If using music writing software, transposing may be somewhat automated.

• Bass flute sounds one octave lower than the written pitch; piccolo sounds one octave higher than the written pitch.

• Depending on the tessitura of the flute 1 part, you might write the part an octave higher, especially if most of the original notes are in the staff.

• Proofread your score against the source material to make sure all notes and rhythms have been transcribed correctly, and that all dynamics and articulations have been added to both the score and parts.

• If some of the notes in the alto flute and/or bass flute parts fall below the instruments’ ranges, change the key to bring all parts into suitable ranges. For instance, if the music is in the key of F major and the bass flute’s lowest note is an F below the staff, all four parts will need to be transposed a perfect fifth higher to the key of C major. Remember to change the key signature in the score and parts as well.

Once the score and parts are complete, invite some flutists to play through the arrangement. If you use a notation program, you can listen to the score through a computer.

As you become more comfortable with the arranging process, experiment with variations for some of the accompaniment parts. This might include changing quarter notes to moving eighth notes or creating rhythmic variations.

Selecting Suitable Works

Flute choir arrangements and transcriptions generally come from some of the greatest music written by composers before 1922. Arrangements are often transcribed or adapted from orchestral, chamber, and choral music (both a capella or accompanied), as well as solo vocal and instrumental music, including piano. Before starting, check online to make sure there is not already an arrangement of the piece you have selected.

Some of the most successful flute choir transcriptions derive from string orchestra works. Arrangements of Baroque flute concertos by composers such as Pergolesi or Boccherini are also good options.

Analyze the piece you want to transcribe. Determine its style period. Each era will be scored somewhat differently. Check the tessitura or range of the piece. As previously mentioned, a change of key may be necessary if many of the notes, particularly for the low flutes, fall below the range of the flute choir.

Decide how many parts your arrangement will have and which flutes you want to use. Study the characteristics of individual members of the flute family to determine how they can be used to best advantage in each specific arrangement.

Part Writing

There are several different schools of thought when writing for flute choir. Some composers and arrangers place most of the melodic material and difficulty in the flute 1 part, with other parts playing a subordinate role. Others prefer to include melodic passages throughout most of the parts. While the results of both arrangements might sound the same to an audience, ensemble members who only play accompaniment parts may become restless and bored.

As a flute choir director for an adult ensemble, I have found that members express the highest satisfaction when all parts contain some moving lines and melodic content. With groups of mixed ability levels, many directors place strong players on each of the parts.

Parts should move gracefully. Omit large jumps and augmented seconds. Watch for parallel fifths and octaves. Do not change the inversion from the original piece. Remember that a second inversion has to be prepared. Learn more about open or close voicing. Be true to dynamics and other articulation marks.

Further Details

Try to keep the same transparency as the original composition. Music can become muddy with too many doublings.

Look up any unfamiliar terms in the original piece. These terms may give clues to help you arrange the piece more effectively.

Scoring choices can help musicians with dynamics. Use lighter scoring with fewer players for soft passages, and full scoring for loud passages. This also provides a welcome change of texture.

Add slurs and other articulation marks where appropriate. Some may differ slightly from the original piece, particularly in vocal, string, and piano music. Apply articulations consistently throughout the arrangement, unless the source material indicates otherwise.

Add cues to help the ensemble, particularly when the first beat of a piece or a new section is silent. In addition, indicate when a measure is silent for all players by marking it G.P. for grand pause. These details will make it easier for a piece to be played correctly the first time.

Readability

Whether you are notating the score and parts on staff paper or in a notation program, make sure that notes and other elements of the arrangements are easy to read and not crowded. Space notes by beat and leave adequate spacing between lines and staves. Crowded notes yield weaker performances.

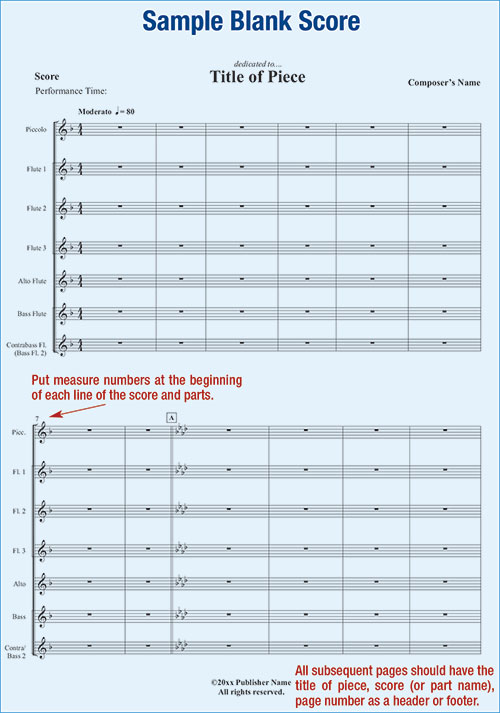

Scores are easier to read when barlines extend through all parts of a system (stave) and font sizes of notes, tempo markings, and measure numbers are large enough to be read easily, but not too large. Depending on the number of parts, there should be two or possibly three systems (staves) on each page. Alternate parts do not need a separate line on the score – for example an optional flute part in lieu of alto flute. You should mark the instrumentation in the score on every page.

Check for readability and page turns when laying out parts as this can be a reason people will not buy a piece. I have seen many scores with tiny fonts and too many systems per page, as well as scores with large fonts requiring page turns every few measures.

Some important final touches are to include rehearsal numbers or letters at the beginnings of a phrases or sections, as well as measure numbers on the left edge of each line of both score and parts. These markings are a time saver during rehearsals.

Consider adding background material about the arrangement and rehearsal ideas in program notes located in the conductor’s score. You should also include the arrangement’s length and difficulty level. Conductors will appreciate these thoughtful touches.

Instrumentation

While there is not a standard scoring for flute choirs, I have found it best to score for six to eight parts, unless the group it is intended for is very large. For those who intend to pursue publication, music scored for fewer parts will have a larger market, as many flute choirs only have enough flutists for one or two on a part and have limited access to low flutes.

I usually score for six or seven parts: piccolo, 3 flutes, alto flute, bass flute, and optional contrabass flute. As a director, I rarely program music with more than four separate flute parts to ensure that all are covered adequately. Many community and student flute choirs have players at various levels, making balance and part coverage more challenging.

General Suggestions

If possible, make sure all parts get the melody, countermelody, or an active accompaniment at some point in the piece.

It is sometimes tempting to give the low flutes all whole notes. Avoid that temptation.

Avoid writing an excessive number of low Cs and low Bs in any part. Many players have flutes with a C-foot, and frequently the footjoints may be not be adjusted well enough to play these notes. Additionally, avoid writing flute parts that only have notes within the first octave.

Writing for Concert Flutes

When arranging for flute choir, writing the concert flute parts is like writing for the violin sections of a string orchestra: there are at least twice as many of them as other members of the ensemble. Most flute choir music has three or more parts for concert flutes, and in most ensembles, there are multiple players, sometimes as many as six or more, on each part. Consider how the flute parts will balance with each other and with the rest of the ensemble.

Keep in mind that notes in the third octave will be the loudest and that notes in the first octave will be the softest. In third-octave sections, consider adding an optional divisi an octave lower to help with balance, particularly in large ensembles. This will also be helpful on long notes to avoid covering moving lines in other sections.

If seeking publication, I recommend including an alternate C flute part in lieu of the alto flute part. This will make your piece playable by a larger number of groups. Some ensembles may not have an alto flute or enough alto flutes to balance the rest of the ensemble. With an alternate alto flute part, C flutes provide better balance for the music. Naturally, some of the lower notes may need to be raised an octave to be in range.

Writing for Piccolo

Scoring for piccolo provides a different tone color that may be used in many ways. Consider the role you would like the piccolo to play in the arrangement. (In some music, piccolo parts may be optional, and others may not have a piccolo part at all.)

The piccolo can be a chameleon. It is able to blend well with the flute section or sit like a cherry on top of a chord by doubling the tonic. It can add sparkle by doubling a melody written in a tessitura that is slightly too low in the flutes to be heard clearly or be a soloist soaring above the ensemble in the first or second octave with a beautiful melody or countermelody.

Avoid writing extended passages for the piccolo in the altissimo range. Some players play these high notes beautifully and in tune, but many do not. For notes above the written third octave C or D, I usually include options to play the passage an octave lower on the same stem. This gives the conductor the option to request the lower divisi notes in certain sections.

The first and second octaves of the piccolo are beautiful. If appropriate, write a section to feature this.

Consider doubling a flute melody with piccolo in thickly scored sections to help the melody come through and give it some sparkle.

Writing for Low Flutes

Unlike concert flute and piccolo where the third octave is the loudest register, notes in the staff are the strongest register for alto, bass, and contrabass flutes. Notes in the high register are beautiful and ethereal with a unique timbre, but may players have intonation challenges on them. In addition, as the softest register, they may be overpowered in tutti sections. Instead, consider featuring some or all of the low flutes in a portion of your arrangement to provide a different texture and tone color.

Over the past twenty years, as flute choirs have flourished, flute manufacturers have improved designs of alto flutes and bass flutes and developed more affordable models. At the same time, they have improved intonation, tone, and ergonomic design. Contrabass flutes have also become less expensive and are available from quite a few manufacturers. Contrabass flutes help balance the treble nature of the flute choir, so more and more groups have made the decision to purchase one.

I strongly suggest adding a contra part to your arrangement – at least an optional part. While the contra part may sometimes have the same written notes as the bass flute part, consider featuring the bass flute without the contra, particularly in softer sections. This change in scoring will provide a welcome change in texture. Another option for the contra, depending on the piece, is to write a lighter part with shorter note values, such as a quarter note with a quarter rest instead of a half note, or sections that imitate string bass plucked pizzicato.

If the contra line is different enough from the bass flute to be integral to the arrangement, consider labeling the part Contrabass Flute or Bass Flute 2. You may also include a bass clef part that doubles the contra, to be played by a cello, bassoon, or string bass. Carefully consider the range in this part, as it may sound an octave lower than contrabass flute, and make sure that it fits with the arrangement.

Voicing and Scoring Suggestions

In my early composing and arranging efforts, Spanish composer and flutist, Salvador Brotons, offered me valuable advice on writing and arranging for flutes. He suggested using open voicing – parts scored with more than an octave between the top and lowest voice. I have found that the richest sonorities are obtained by using this idea. When root position (or close voicing) chords are used with full flute choir, the results can sound muddy and indistinct. Music scored for more than seven to eight parts can also be muddy because of the homogeneous sound of the instruments. When transcribing from orchestral or other large ensemble literature, it is tempting to transcribe literally. It is up to the arranger to use doubled tones and octaves sparingly to create the most flattering sound for the ensemble.

Final Touches

Proofreading is an essential step to getting a score and parts ready for performance. It is frustrating for groups to spend valuable rehearsal time fixing wrong notes and rhythms. Music notation software with playback capabilities help composers check for correct notes. However, a careful eye and patience is required to ensure accurate and consistent articulation and dynamic markings throughout all the parts.

When nearing completion of an arrangement, play through each of the parts to discover wrong notes or notes that a player might perceive as incorrect, as well as confirming readability and consistency of articulation and dynamics. It is also important to see whether each part will make sense to players when practicing, as well as in the context of the score.

Occasional well-placed courtesy accidentals will be a timesaver during rehearsals and appreciated by the group and conductor. Doublecheck that all notes are within the playable ranges of the flutes. I own quite a number of publications with notes that are outside of the flute’s range, such as Bb or A below the staff.

Within the United States:

1. Works published in any country from 1922 and earlier are public domain in the U.S.

2. Works published in any country from 1923 through 1977 are protected in the U.S. for 95 years.

3. Works published in any country from 1978 onward are protected for 70 years after the death of the composer or co-creator (poet, orchestrator, etc.), whoever lives longer.

4. The above covers most music and methods, but there are some exceptions and more complicated situations for posthumous works, and some works created for hire.

In all other countries:

Outside of the United States, most countries follow either death of creator plus 50 years (including Canada), or death plus 70 years (including most of Europe), but there are differences and exceptions in some countries.

For 20th-century composers, there are many works that are public domain in some countries and protected in others. For example, Gershwin from 1923 onward is protected in the U.S. and public domain elsewhere. Stravinsky from 1922 and earlier is public domain in the U.S. but protected elsewhere.

Submitting Music for Publication

Research which publishers have flute ensemble or flute choir music in their catalogs. Be sure to contact publishers prior to submitting your manuscript. Find out specific submission requirements and deadlines and whether new submissions are being accepted. Include a description, timing, and instrumentation of your piece to determine whether it is a good fit for the publisher’s catalog.

Most publishers only accept submissions that are typeset with music notation software such as Finale or Sibelius. In addition, most require that submissions include score, parts, and a recording. It should be either original music or an arrangement of music in the public domain. Some publishers prefer submissions be submitted by mail, while others will allow email of pdf files of score and parts and an mp3 recording. For most publishers, the standard royalty amount is 10% of the retail price.

Self-Publishing

Many composers and arrangers set up a website to market and sell their music. If you decide on this option, the website should include information on instrumentation, difficulty level, duration, program notes as well sample pages of the score and an mp3 recording of the piece. You can opt to send customers printed music or offer a digital download. Selling digital downloads has the advantage of not requiring shipping, which means customers can buy the music from any place in the world. Some flute specialty shops sell printed copies of self-published music.

Another option is to sign on with one of the internet publishing companies. The composer provides the publisher with a score and parts through in a digital file format as well as the same background information about the work. The publisher makes the music available for sale, collects payments and facilitates the digital download of the music to customers. The publisher will also offer advice for pricing depending on the scoring and length of the piece. In return, the composer receives a pre-determined royalty on a monthly or yearly basis.