The Broadway musicals Wicked and The Lion King are iconic shows that are recognized worldwide for their longevity and popularity, while consistently ranking atop New York City theaters’ weekly box office grosses. Both have generated numerous stagings; currently they have national and international tours along with parallel productions in Mexico, Brazil, China, Japan, Germany, The Netherlands, Spain, and England. The current original Broadway productions, however, are the flagships for their brands and a benchmark against which all other productions must measure. Helen Campo has been the flutist of Wicked since its first bow in 2003, and David Weiss has been the flutist of The Lion King since its premiere in 1997. Although they have Broadway in common, their careers exemplify the eclectic variety of opportunities for New York musicians.

In statistics provided by The Broadway League, the 2015-2016 season alone saw Broadway shows grossing $1.37 billion to an attendance of 13.3 million, providing over 89,000 local jobs, and contributing $12.6 billion to the economy of New York City on top of ticket sales. In addition to their Broadway work, many pit orchestra players are involved in the myriad facets of the New York City music scene including performing with classical organizations such as the New York Philharmonic, Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, and Orchestra of St. Luke’s; playing in various avant-garde new music powerhouses; recording soundtracks for television shows, commercials, and film; backing visiting musical acts on late night talk shows; and holding faculty positions at conservatories and music departments. With a Broadway schedule of eight performances a week and only one full day off, their lives are a study in time management and organization.

Broadway shows often pride themselves on the size of their orchestras (the recent revival of On the Town was advertised extensively with the tagline “The biggest orchestra on Broadway”) as a further way to broadcast the production’s commitment to producing a full-scale display for the audience. The pits of The Lion King and Wicked are on the larger side for Broadway orchestras, with each having 23 musicians plus a director. An expansive orchestra adds to the gravity and extravagance of a production and is sometimes directly incorporated into the action on the stage. Chicago and Jersey Boys both feature on-stage bands, and the recent revivals of South Pacific and The King and I at Lincoln Center Theatre included sets that were specifically designed to highlight the orchestra members.

Flute in Pit Orchestras

Many Broadway orchestras include a woodwind section that is comprised of doublers who can play on multiple instruments. On other occasions, the music supervisor, producer, composer, or orchestrator may seek a traditional full orchestral sound, or possibly a very distinct ethnic flute inflection. In these cases, they may write a flute-specific part.

Broadway musicals that feature a dedicated flute book include Cinderella, The King and I, South Pacific, The Sound of Music, Fiddler on the Roof, Les Misérables, Beauty and the Beast, Miss Saigon, Aida, Ragtime, Mary Poppins, and Finding Neverland, to name a few. There has been a trend in revivals of classic musicals to utilize their original orchestrations which usually featured more performers and more classically orchestral instrumentation than subsequent incarnations. There are also a number of new musicals that use international flutes.

Even parts written specifically for a flutist, however, usually call for the player to double on other members of the flute family. This often goes beyond the standard orchestral doubles of piccolo or alto flute. In Wicked the flutist plays recorder, tin whistle, flute, piccolo, and alto flute, while The Lion King calls for thirteen flutes, including several wood flutes in various keys, South Asian bansuri, Eastern European pan flutes, and a South American bass pan flute (the Toyo, which is 4 feet tall), in addition to flute and piccolo.

There is only one designated flute book on Wicked (in the Playbill, Helen Campo is billed as flute), but there is another woodwind player who also plays some flute. Wicked has four woodwind books: flute, oboe/english horn/bass oboe, Bb and Eb clarinets/ bass clarinet/soprano sax, and bassoon/baritone sax/clarinet/bass clarinet/flute.

The Lion King has two woodwind players, but David Weiss is the only one with a designated flute book (in the Playbill, he is billed as wood flute soloist/flute/piccolo). The other woodwind player mostly performs on clarinet and bass clarinet but also plays some flute and is billed as flute/clarinet/bass clarinet. For flutes in different keys, Weiss devised a system where the music is notated with a double staff. The top staff has the transposed part, and the bottom staff shows the concert pitch, making the intended sound clearer for both the woodwind specialist and the music supervision team. This system has been adopted by many productions worldwide since he began using it in the 1990s.

In general, blending and listening in a pit orchestra can be a challenge, since the space is usually acoustically dead. Every player has a microphone that has been chosen and balanced by the sound designer, and the sound levels can be adjusted in real time by the production audio engineer. Pit musicians balance what they hear happening around them with what is being broadcast through the house audio. To help with this, they can calibrate what they want to listen to through personal sound mixers that are used on many Broadway shows. This personally adjusted audio can be heard by the musician on nearby speakers or headphones.

Helen Campo and Wicked

Helen Campo and Wicked

Wicked is based upon the 1995 novel Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West by Gregory Maguire and takes an alternative view of the relationship between the Wizard of Oz’s Wicked Witch of the West and Glinda the Good Witch. Featuring a score by Stephen Schwartz that includes such modern classics as Popular and Defying Gravity, the work showcased its original stars Kristin Chenoweth as Glinda and Idina Menzel as Elphaba (the character who would later become infamous as the Wicked Witch of the West).

Helen Campo is the original flutist of Wicked. In addition to her Broadway position, she is principal flute of the New Jersey Festival Orchestra and a member of The New York Pops. She is also a long-time principal substitute for the NYC Ballet, NYC Opera, and NY Philharmonic. Campo began playing flute to follow in the footsteps of her older sister, and progressed rapidly, becoming the youngest flutist ever to have won the Concert Artist Guild competition. Immediately after graduating with an MA, she was hired by Loren Glickman to play the summer season at the Metropolitan Opera, which was providing ballet music for out-of-town companies such as the Kirov and Royal Ballet among others. The principal flutist there was Andy Lolya, who recommended her to a Broadway contractor, and the rest is history. Wicked is her 11th Broadway chair. She teaches privately, both in Manhattan and over Skype, and is married to cellist Danny Miller.

In addition to her regular flutes, Campo plays an alto flute, piccolo, soprano recorder, and Eb penny whistle for Wicked. She also has a collection of penny whistles, bamboo flutes, Irish wood flutes, and pan pipes. “Notation issues for most of the instruments I play are minimal; you just have to know that a lot of these instruments are not in C, but instead of transposing you think in concert pitch and consider the fingerings to be different for the same pitch on the different instruments. If one is very flute-centric and not used to thinking of fingerings being totally different on the differently keyed instruments, one can always just transpose.”

She comments that one of the most noticable differences between performing in a Broadway show versus in an orchestra is the complexity of the flute parts – although a notable exception to this is the music of Leonard Berstein. “I was fortunate enough to play under him at the age of 20 in the Tanglewood Fellowship Orchestra and not long after play flute and harpsicord duets with him. At its essence, however, music is music whether playing symphonies or Broadway shows. There is always an opportunity for expression and dialogue. Certainly, the flute parts in symphonic repertoire are far more complex than Broadway flute books. With the exception of the highly chromatic recorder sections in Jane Eyre, I have never played a Broadway flute book that could not be sightread. On the other hand, chamber and solo flute repertoire tends to be more demanding technically than orchestral repertoire.

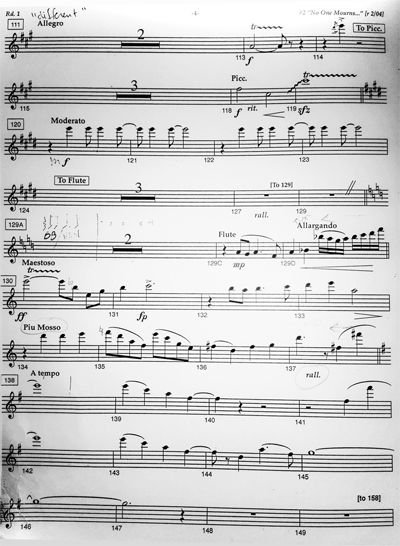

Page of flute part of Wicked

“Playing technically complex music is a great deal of fun, in the same way that figuring out a puzzle is fun, but it does not necessarily make the musical experience more profound. For me, communication is what is most important – whole worlds can be expressed in one note or in the silence between two. Conversely, sometimes nothing is expressed in a thousand. This is not to say that a thousand notes cannot be expressive as well, but complexity is independent of expression. So, if you remember that while playing, the particular genre becomes less important.

“I think that attitude allows me to just be very grateful I am performing whatever it is I am playing at any given moment. Granted we have to play the same music over and over, but that happens in an orchestral setting as well. In the 12 years I subbed at the New York Philharmonic, I played some Tchaikovsky symphonies enough times to make your head spin. Even when I was 20 and on the Concert Artist Guild roster as a soloist, I experienced a lot of repetition. It seemed as though everyone wanted me to play the same two concertos with their orchestra. I remember thinking while on the road during that period that it was sort of like a Broadway show – only with jet lag. Repetition and simplicity can be your ball and chain on a Broadway show, or with the right attitude, they can be a musical zen experience, and simplicity can equal freedom.”

David Weiss and The Lion King

David Weiss and The Lion King

The Lion King caused a sensation when it opened in 1997, with visionary director Julie Taymor taking a beloved Disney animated film and reimagining it by incorporating stunning puppetry and costumes. The South African musician and composer Lebo M added Zulu musical numbers and lyrics to the original songs by Elton John and Tim Rice and the Hans Zimmer score. This greatly enhanced the theatrical experience and further established the stage musical as its own unique entity. The Lion King has won six Tony awards including Best Musical and Best Director, and is currently the third longest-running show in Broadway history and the highest-grossing Broadway musical of all time at over $1 billion.

David Weiss has been flutist for The Lion King since its pre-Broadway run in Minneapolis during the summer of 1997. A highly sought after clinician on world flutes, he has given presentations at several National Flute Association conventions and co-composed the woodwind parts on The Lion King. He was instrumental in writing and notating for the various world flutes integral to the score.

Weiss comes from a musical family. His mother was a flutist and teacher who studied with Joseph Mariano and Julius Baker, and his clarinetist father (now retired) was an Associate of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra for decades, with an illustrious career bridging the Classical and Broadway worlds. Weiss earned a university degree in classical flute performance but is also an experienced jazz musician. Growing up on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, he was exposed to the music of various international cultures. By his high school years, he was exploring the flute music of Japan, India, Latin America, and Africa. This would lead to a lifelong interest in international instruments. Over the years he has amassed a collection with hundreds of flutes and other woodwinds. Composers and orchestrators often consult with him on historical and ethnomusicological matters, and he lends his expertise to film soundtracks, television commercials, video games, and documentaries, among other projects.

Weiss began performing as a substitute on Broadway while still studying at the Manhattan School of Music. His first job as a regular on Broadway was with a production of Shakespeare’s All’s Well That Ends Well, and in 2017 he will mark his 20th anniversary working with The Lion King full-time. Over his career he estimates that between Broadway and Off-Broadway he has had 13 shows of his own and performed as a substitute on around 35 others. He is currently working on an etude book that concentrates on visualization of certain exercises, which serves as a basis for learning to improvise. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife, violist Kaya Katarzyna Bryla.

Even though pit orchestra musicians can play the same show for years on end, live theater provides enough variables, both onstage and in the pit, to demand a player’s full attention and musicality. Whether it be a new understudy going on for the first time, or a substitute musician joining an established section, there are always things to listen and watch for. Every show may not have the excitement of opening night, but they have the responsibility of presenting the show in its best form for each new audience. Helen Campo and David Weiss embody this ideal in every performance.

* * *

Tips for Playing in a Pit Orchestra

Protect your hearing: Performing in such close and enclosed quarters, it is important to always keep hearing protection in mind. Occasionally playing with ear plugs (in one or both ears) can take some getting used to, as it obviously greatly alters the musical lines you are used to hearing. Slight discomfort aside, it is much preferable to permanent hearing damage. I have seen everything from sound blocking ear muffs to custom molded earplugs utilized in pits in addition to the regular kinds you can buy at the pharmacy.

Layers: Pit temperatures can fluctuate wildly from day to day, and even during a single show. In addition, stage effects such as theatrical smoke and fog often drift straight off the stage and right into the pit – instantly affecting both temperature and humidity. It is helpful to have an extra layer of clothing (black) for these situations. It is also crucial to take note of the effect these fluctuations can have on your instruments and adjust accordingly.

Basic Repairs: Anything can happen during a show, from stage props falling into the pit to keys binding from temperature drops. It can be invaluable to have basic repair knowledge and tools on hand, such as spring hooks, screw drivers, key oil, pad paper, etc. Of course it is better for a repair technician to take a look at your instrument, but for last-minute problems these items can save a performance.

* * *

Mishaps

Live theater can lead to occasional hiccups when something does not go according to plan. While playing in a revival of The Sound of Music, Campo recalls Maria’s bicycle falling off of the stage into the pit. “No one was hurt, so we all oohed and aahed, handed it back on stage, and kept playing.” She was also playing in a show when the conductor fell unconscious during the performance. “We had to call an ambulance. He was taken away still unconscious, but turned out to be fine – just dehydrated and weak from working out too much.”

During the time Weiss was with Miss Saigon, he was seated on the edge of a shallow orchestra pit with just a curtain and a rail between himself and the first row of the audience. “The audience was about three feet above the pit, and some people would poke their feet through the curtain and hover them above our heads. I got tired of this and got a feather quill so if someone invaded my space a bit too much I would tickle them with the feather quill to get rid of them.”