Thomas Robertello’s creative interests range from solo and orchestral performing to teaching at the college level and owning an art gallery. Currently the associate professor of flute at Indiana University, Robertello has been a member of the National Symphony, The Cleveland Orchestra, and the Pittsburgh Symphony and served on the faculty of the Asian Youth Orchestra, Carnegie Mellon University, University of Notre Dame, Roosevelt University, and the Cleveland Institute of Music.

What first interested you in the flute?

When did you decide on a career in music?

In my early teens I knew I wanted to be a teacher and orchestral musician. I listened to WQXR a New York City radio station, every Saturday morning for a few hours, admiring the beauty of what I heard but also annoyed by the theme music every week, which was the opening of the third movement of Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony. The first phrase of eighth notes in the strings was marred by a mordent, and the theme music would stop before the return of the next mordent, so naturally I thought it was a mistake! I remained unfamiliar with the piece for years, until one day what had always sounded like a mistake to me was suddenly a mirror reflecting my deep ignorance. To this day I vibrate every note after mordents or grace notes to remind myself to show the music clearly for the uninformed.

The first orchestra concert I attended was the Boston Symphony playing Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in New York. I was thrilled to learn that the flutes were in the center of the orchestra. I remember hearing the electricity in principal flutist Doriot Anthony Dwyer’s tone and feeling very inspired. I was also informed that I should not clap between movements in a symphony, so when I read in the program that there were four movements, I pledged not to applaud and to be on my best behavior and fit in with the sophisticated NYC audience. After I counted three movements, applause broke out. Thinking everyone must be wrong but me, I did not clap right away. It was another ignorant moment because I was unaware that the third and fourth movements were played without a break. The lovely segue into the fourth movement was not the silence I was expecting. I had many of these moments as a student, and they led me to study music more deeply and read scores.

Who were your teachers?

I went to Juilliard from 1984 to 1986 and left in the middle of my junior year to join the National Symphony. While there I studied with Julius Baker and Jeanne Baxtresser. Prior to attending Juilliard, I took lessons with Paige Brook, who at the time was the associate principal of the New York Philharmonic. I should say that I was mostly unteachable. I appreciated everyone’s playing but was not always clear on how I could be helped. The good thing is that none of my teachers really taught me how to play the flute differently. They all helped me to find my voice, my sound, take responsibility for my own preparation, and offered a lot of positive energy. I studied with Baker for two years and absorbed a lot of new repertoire and then switched into Jeanne Baxtresser’s studio where I focused on finding greater discipline in my practice and deeper attention to an array of details. I cobbled together many ideas and used them to further my own concepts.

As a precocious high schooler, I once arrived at a lesson and informed a teacher that it was our final lesson. He asked why, and I replied that I needed to play music the way I heard it and was taking a break from being influenced by others. The teacher of course laughed at the ridiculousness of my comment, but there are times when one should say they just want to play and not be influenced by others. I think that is perfectly legitimate and I look forward to the day when someone says it to me.

Now I am constantly inspired by violinist Hilary Hahn. Her recordings give me endless pleasure. I am enthralled by the artistic and musical choices she makes. She has an endless wellspring of options and knows how to edit herself. When considering the level of sophistication an artist obtains, I find it so important that one makes singularly committed interpretations. One has to find the right way of saying everything, and the end result comes through the process of having considered and rejected almost everything. To chisel an interpretation that is long lasting, full of surprises, which very often subverts expectations (and for some disappoint), offers great meaning. When I listen to her play Bach or Ives it is just the best music-making I have ever experienced. I find many musicians with complete command do not know how to edit themselves, so I feel like I am listening to everything at every moment in all repertoire. Something can sound overwhelmingly wonderful at first but on repeat listening, it loses its patina. The saying “just because you can doesn’t mean you should” rings true for me.

Many conductors have influenced me when their interpretations brought me beyond my limits. In an orchestra one has to be so flexible and quick to respond appropriately to their demands.

Were you always interested in a career as an orchestral musician?

Yes and No. This is a question I have never been able to adequately resolve. I have always wanted a career as a flutist and musician though. That was never uncertain. When you put your life on a path and decide every day to keep moving forward without looking back, the world will open up to you and recognize that quality. I did not always know that I wanted a career as a college professor, but once those opportunities found me, I was hooked.

What is the key to winning an audition?

Pleasing a committee and conductor is most important. Anyone involved in the process of auditioning should realize that they proceed forward at the pleasure of the committee. Certainly there are basic issues that must be sorted out. Rhythm, intonation, articulation, tone quality, and musical choices are generally the areas of evaluation in the audition process. Rhythm and intonation are non-negotiable. Those qualities are the common denominators in an orchestra. They must be at the highest level. Articulation styles are less rigid I would say, but the clarity and timing of the onset of notes are crucial.

I am convinced that one can have any tone quality and still win an audition. There are so many different flute tones these days that I find wonderful, but in an audition, beautiful tones can come with bad rhythm and diffuse tones can come with flawless intonation. The variety of flute sounds can make evaluating musicians very confusing for a committee assembled from different sections in the orchestra. Still, the musical voices who can play commanding solos and blend like a chameleon when necessary and who have utter control over their instruments will rise to the final round. Musically, it is important to make distinctions in the style of sound, vibrato, even rhythm from excerpt to excerpt. Being well-informed is often the key. Knowing the role or function of your excerpt in the larger context and hearing the passage of harmony while playing can be very convincing.

What were the similarities and differences in the various major orchestras you played with?

Well, they are all completely alike and different simultaneously. The players are all different, but the demands of the repertoire and the need to find an exquisite balance between solo and tutti playing carry over everywhere I have played. There is a great need to be a flexible negotiator in a non-verbal way in every orchestra. Orchestras are shaped by individual music directors. When I have been a guest with some orchestras, I have noticed huge differences when they play for their conductor or a guest conductor. The musicians are conditioned to certain expectations, and when those expectations are clear, it is easy to figure out your job, even though it might be difficult to achieve it. In every orchestra I was always fully prepared to the best of my ability, but I also always went away after the first rehearsal thinking I had to change everything by the next morning. Sometimes the changes felt so extreme to satisfy the interpretation of the conductor that I wished for more time, but I have seen some amazing transformations in orchestras from the first rehearsal to the first concert.

What suggestions do you for young flutists who are new to playing in orchestra?

Piano, piano, piano. Much of the job involves flawless control over the softer dynamics. Give yourself room to grow. It is more prudent to be somewhat guarded at first and have to scale upward rather than scale downward. That goes for behavior too. To an outsider, orchestras can seem like very conservative environments but often it is really that everyone is just focusing all of their attention on every nuance of timing, mood, dynamics, etc. This quiet intensity can seem nerve-racking at first but later becomes more meditative. It is important as a newcomer not to disrupt this undercurrent in any orchestra.

Do you have a specific teaching curriculum for undergraduate students?

Typically for first and second year undergrads we work on foundation issues. They have weekly Taffanel & Gaubert classes and have to pass a proficiency by playing exercises 1, 4, 5, and 6 from memory. There is always work on embouchure choices, breathing techniques, intonation, vibrato, etudes, and standard repertoire. During the second half of their undergraduate degree, the focus turns more heavily toward solo repertoire, in preparation for junior and senior recitals. Weekly work with pianists becomes a necessity. Etudes and exercises remain part of weekly practice, but I refer to them to resolve issues I hear in their repertoire. Marcel Moyse’s De La Sonorite is one of the go-to tomes.

When we work on etudes and exercises, I emphasize listening skills and responses to changes in harmony. As single-note melodic players, young flutists are sometimes unaware that their notes belong in a larger harmonic context and compositional structure. I will often sit at the piano and play chords. For example, I will play a G minor chord and ask them to play G and then repeat in G major. I ask students to respond with color or vibrato choices, intensity or expression on a single note that suits the character of each chord. Through that process they become much more sensitive to fitting their lines into the harmonic context. This develops an artistic intuition and freedom to make personal choices that are appropriate to their repertoire.

What is the goal for graduate students?

They also must attend a T&G class and pass a proficiency jury. I have found that the beginning of a graduate degree requires making sure the basics were fully integrated previously. I strive for a musical approach to the T&G exercises so they are not played lifelessly, but rather with enjoyment of the beauty of scales and arpeggios. Often the first semester of each year is heavy on technique and etudes and light on repertoire because spring semester recitals require focusing only on repertoire.

How do you teach excerpts?

It is a really long process and requires students to develop skills of self-education. At most, a teacher works with a student for only a few hours a week in a lesson, masterclass, or excerpt class, and that is a limited amount of time to foster the rapid development needed. Much like learning solo repertoire, excerpts require slow practice, recording oneself, score study, and also listening to orchestras (preferably live) so that the context of each excerpt is clear. I advise anyone taking auditions to create a list of 20 or more excerpts, work on three per day in great detail, recording, polishing out small flaws, and listening for rhythm, intonation, and vibrato. The next day, they should focus on three more, but use the previous day’s excerpts for a play-through test. Don’t practice them; simply play them through, changing up the order each time, and making mental notes about what to fix later. It is important to put structure into practice time and to keep all of the excerpts in a weekly practice routine. This will make them easier to play at a summer festival or professional audition. It is also important to play them for small groups of people regularly. Organizing excerpt groups with multi-instrument groups is valuable in school and afterward. The year after graduation is crucial for determining how a career might develop. Without the structure that school provides, many musicians find themselves floundering unless they put a strategic plan in place that allows for time to practice and also maintains connections to others with similar goals.

What led to your recording of the Telemann 12 Fantasias?

In my mid to late 20s, I started examining how I played much of the standard repertoire that I had learned in high school. This included revisiting Bach and Handel sonatas, typical French pieces, Mozart concerti, and these Telemann Fantasias. Contrary to what seems de rigueur these days, I do not find vibrato-less tones appealing for entire collections of sonatas or fantasias, except maybe as a tool for the player to develop core control in the privacy of the studio. The discipline required to maintain that position should not be considered an artistic endgame strategy. Rather, carefully considered vibrato choices (no vibrato at times being among them) can carry the music in more directions emotionally and provide a wider palette of colors. There is no shortage of bad vibrato choices today as well as during the 18th century when critics of the practice handed down sets of rules and regulations to follow. Much like religious material, these words can be interpreted to suit any number of positions on the subject. That it was written about at all provides documentation of its existence. People now choose sides on the issue, often at the expense of investigating further possibilities, subtleties, and nuances.

How do you help students preparing for auditions?

When a high school student comes for a lesson, I always ask what their weekly practice is like – exercises, scales, tone, etudes, and repertoire. I also want to know how long they have been preparing a piece or for how long they plan to study it. Mostly, they need structure in their daily fundamentals – which exercises, how long for each, what to listen for, etc.

I also find that many students play the same two pieces for six months or longer, becoming entrenched in their weaknesses, steeped in bad habits. This is such a lifeless way to approach music. Often they are engaged in competitions that do not benefit their playing. They are not developing enough sightreading skills and do not play repertoire for fun. They should be encouraged to play level-appropriate pieces that they can digest quickly, while simultaneously tackling more substantial repertoire. It is so deadening to work on the same piece for six months to a year to polish it when their musicianship is not being developed.

When students come to audition, it should be understood that they will be accepted on the basis of potential and not finished product. The worst thing a teacher can do is force them to polish something before developing it. It is suffocating for them.

How have students changed in the past 20 years?

Grade expectations have certainly changed. When I was a freshman at Juilliard, I received a B minus for my jury, which was a compilation of all three professors’ grades. It made me realize that I had to get my act together. I took full responsibility, never questioned it or blamed anyone else. I bounced back, worked hard, and the next year got an A. In the current climate of music schools needing to function as for-profit businesses, enrollment numbers are higher and so are student expectations. The range of quality is greater but grades do not always reflect that. They tend to reflect effort or intentions rather than actual performance level. Some students believe they deserve an A grade just because they try hard and do not have a realistic picture of themselves and how their work compares to the overall levels. I have given B’s and even A minuses only to be met with requests for a grade change, simply based on their effort and not the quality of their work. Professors often acquiesce to these demands. I have received phone calls that sounded like they were from a guest at a luxury hotel, “Excuse me, you messed up my room service order, I want an A please.” We are witnessing, as teachers, the zenith of many of their careers, not the start of them, and so some want that marked by a pristine GPA. It does not give them the chance to self-evaluate when faced with a challenge and does them a great disservice in the long run.

Self-education is another way in which opportunities have opened up but confusion abounds. I only wish as a student that I had had access to YouTube and other ways of connecting with a multitude of flute recordings and orchestra performances. Many students, however, do not know how to employ discerning tactics when searching for material, or take for granted its availability and therefore do not use it. So much information is so readily available that many do not know how to process it quickly, so they access too few, none at all, or the same people over and over. There are great ideas all over the Internet, and I am constantly baffled by the choices people make to limit their exposure to the hidden gems. As a demonstration in a lesson recently, I went to YouTube to see how many people had Nielsen Concerto recordings. I was amazed by the number. If you search “Nielsen Flute Concerto,” dozens of great players come up before you might see what is arguably the best recording of the work. It is one made by Julius Baker and has only about 197 views.

I also see the normalization of students (and sometimes misguided teachers) providing pharmaceutical advice and medication to each other, specifically beta blockers, which are now widely used to lessen performance anxiety. It has become so commonplace that few consider the potentially serious physical, legal, and even musical consequences of sharing prescription pills or advice regarding their use. A normal dosage for one person might be three times the amount needed for someone else. There is also a risk that when someone takes them for the first time to get through a recital or audition, they find that their senses and skills diminish, and a dullness takes over. I have seen months of solid preparation fly out the window. If medication is needed for any issue, including performance anxiety, that should be taken up with a physician and not a fellow flute player.

I wonder if this current reliance on medication is an avoidance of momentary failure instead of addressing an underlying issue. Becoming a musician is a risky business. While we know this on an intellectual level, when the stakes are high, we tend to lose our sense of adventure. Self-medication at early stages may strip away opportunities to grow through difficult experiences. An immediate fix does not usually produce fruitful results in the long term. It may be helpful for teachers to share with students some of their own vulnerable moments and how they got through them. The connection this produces can provide a safety net that allows students to make space for all aspects of their experience, instead of feeling they have to hide or control difficult feelings. I have had lots of great professional opportunities. The best ones occurred, usually taking me by surprise, after I turned 40 and had previously left unspeakably awful noises in concert halls worldwide. My best advice: fail. Take a chance. Fail harder. Bounce back. Keep going.

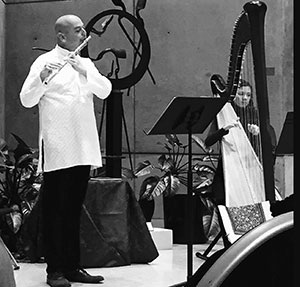

Performing ragas by Sameer Rao at the IU Art Museum

What is your teaching philosophy?

School is an excellent place to make mistakes. I am here to provide a space for those things to happen and build tools to problem solve. I encourage people to assume their first choice is often the worst choice; therefore they should create several disparate choices for one thing and choose the best. After selecting one, the next step is to carry that choice forward and create a few others. It becomes a step by step forward moving process so students learn to think beyond their initial reaction to something. There is great power in having choices and weakness in having only one. I see every note and phrase as an opportunity to exercise artistic choices. When students see that as their responsibility, they listen, think, and react differently. Nerves diminish because they have already confronted so many things by the time they present on a stage. Independent personalities develop, and while I demonstrate frequently in lessons, none of my students sound alike or like anything that resembles my playing.

How does painting complement your flute playing?

Painting, much like any outside interest, allows freedom from judgment to enjoy what you want to do. If you are free from judgment, even when you are being judged, then you are in possession of your work. When I painted in my 20s, I felt free, even though my paintings were mostly bad. I learned a new skill, and that was seeing. This is different from reading in that a deeper part of the mind is engaged. When I incorporated seeing with music, as opposed to reading it, I understood composers’ intentions differently. I started to feel a purpose for the notes. Waves of sound become possible; moments became longer; and I began to understand compositions as drawings that contained a sense of urgency, so emotions flowed more freely. I started collecting art and using it to inform my ideas about music. I would often walk around a room and play the colors, shapes, and lines that I saw. Music, being among the most abstract art forms, had been mostly technical for me until that point. I could only understand it through technical execution. Once I paired visual abstraction with my understanding of the flute and music, it opened a new level for me. I was particularly influenced by the writings of Agnes Martin, a minimalist painter whose work interests me. She said, “Even the bad paintings need to be painted.” This always stuck with me as I practice many unusable tones on the flute because they give me better choices and help me understand the instrument better. Take harmonics for example. These are the primary colors on the flute. When I ask a flute how it wants to play, I always check with the harmonics. I play what I call dirty harmonics, which are closer to multiphonics. I will float on a harmonic, let it sink to the next lower harmonic, play in the space between them, embrace their instability, and later allow the new striations of color to infiltrate my tone. Complexity in tone requires the ability to deconstruct and reassemble. Essentially, we are drawn to things outside the flute that also need our attention. Making space for them expands our understanding and artistry.

After collecting contemporary art for about ten years, I wanted to open a public space for people to view the art that interested me. This happened when I turned forty. I wanted to participate in a public dialogue about visual art and work with young artists at a time when I had gone through a crisis about deciding whether to parent. Adoption laws were not on my side at the time, and after much consideration, I gave up a longstanding goal to adopt children and opened a gallery in Washington, DC, which I moved to Chicago one year later in 2006. I operated the gallery for eight years and am very proud of the artists who agreed to have exhibitions in my gallery.

Do you still own the gallery?

Things had gone very well. I was comfortable with publicity and was able to reach out in an effort to promote other artists’ work with an ease that I had never felt promoting my own work. I felt torn after some years because I was working very hard maintaining the business, teaching, playing, and travel. In 2013 I took a teaching sabbatical and went to India to study the bansuri (bamboo flute) and Hindustani music with Sameer Rao. My goal was to learn to play the bansuri well enough to be able to translate its music to a Western flute. I recorded Sameer playing several ragas, with the idea that later I would transcribe them into Western notation in order to make them playable on the flute as fixed compositions. Hindustani music is so rich in tradition and predates all the Western music we play. However, unless one studies in India, this music is completely inaccessible. I feel the project was a huge success and have now completed three of the six compositions. I hope to publish them soon. After this experience, I returned to Chicago and informed my gallery staff that I would close the space and go back to having one career instead of two.

After I closed my gallery in 2013, I spent more time at home in Bloomington, and the earlier wish to become a parent returned. Initially I became a mentor for Big Brothers and Big Sisters for two years. I was matched with a very special child who later decided to play the flute and now is enjoying band. Then, I started fostering some kids. Finally, adoption laws changed, and I was able to adopt directly from the foster care system. A few days ago, I adopted my son Michael, who has been living with me in foster care since June 2017. He turned 11 the day before the adoption. Now I am hoping to foster or adopt a second child.

Robertello has given masterclasses and performed as a soloist throughout the United States, Europe, Japan, South Korea, China, and South America. His many festival performances as a soloist include the Pacific Music Festival (Japan), Sarasota Music Festival (US), Grand Teton (US), Nara (Japan), Kirishima (Japan), Londrina (Brazil), Dartington (UK), Athitos (Greece), Music Anatolia College (Greece), Brevard Music Center (US), National Orchestral Institute (US) and Euro Music Festival and Academy in Halle, Germany.

He has recorded extensively for the flute. Recordings include the Telemann Twelve Fantasias, Bach Solo Works for Flute, Souvenir: Music by Faure, and commissioned contemporary works by Martin Kennedy, David Dzubay, Mischa Zupko, Matthew Van Brink and Winston Choi. Most can be found on his YouTube channel: www.youtube.com/user/ThomasRobertello

Every year I send my students a list of etude books I learned before age 25 so they have some idea about what a long-term process might look like.

Andersen Op. 15, 21, 60, 63

Bach 24 Concert Studies

Berbiguier 18 Exercises

Boehm Op. 37

Bozza 14 Etudes-Arabesques

Chopin (Moyse) Etudes

Donjon Etudes de Salon

Genzmer 24 Etudes

Jeanjean Etudes Modernes

Karg-Elert 30 Caprices

Kreutzer (Moyse) Etudes

Paganini 24 Caprices

Piazzolla Tango Etudes

Wieniawsky (Moyse) Etudes