When teachers point out technical flaws during lessons, students may devote hours of practice to correct these problems which are often the effects of basic playing habits. Erratic trills, hyperextended fingers, and uncontrolled fingers often result from poor hand position.

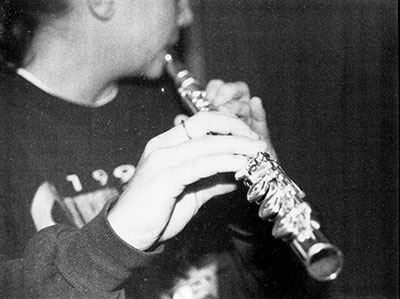

Despite the physical variances among flutists, most players do better if the flute is held in front of the body in a left-looking position. Here the wrists and fingers can relax while supporting the flute. The fingers can move easily when the flute is balanced between the chin, the base of the left-hand index finger, and the tip of the right-hand thumb. If the flute is turned outward with the tops of the keys pointed away from the player, the left-hand keys are easier to reach and the weight of the mechanism is centered on top of the flute.

The long mechanical rods and key work make up the heaviest part of the flute. When they are positioned on top, over the center of the tube, the flute is more balanced and will not roll in toward the player. If the rods are rotated in from the center of gravity, they will pull the flute in too much causing the player to cover too much of the embouchure hole.

Flute playing takes hand and arm strength, which can be developed by piano playing, light weight lifting, and isometric hand exercises.

On passages that use complex left-hand technique, such as the second movement of the Bach Sonata in C Major or the Chaminade Concertino, the flute tends to move around on the chin, especially on jumps between the first and second octaves. If the flute is supported with the three balance points movement is minimized. The right-hand pinky should not be used as a fourth point of support.

Left-hand trills from G-A and A-B, such as those in the Mozart concertos or Reinecke’s Sonata, are often slow or erratic because the fingers and thumb grip the flute instead of just closing and opening the keys. When using a left-looking position, if the torso is turned to the left with the left hand in front of the chest, these trills will be easier to play.

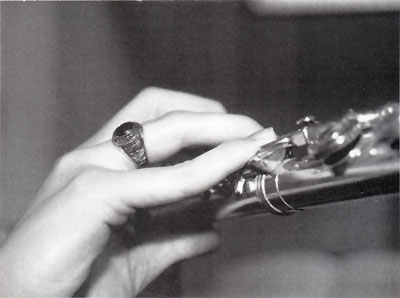

The Bach Sonata in E flat Major, Godard’s Allegretto, or Taffanel’s Andante Pastorale et Scherzettino call for smooth movement of the left-hand index finger to play the second octave D and E flat. For greater index finger movement, move the left wrist under the body of the flute and turn the palm outward.

Avoid locking the right-hand pinky as this causes stiff and jerky breaks in slurred passages. On such passages, as the opening of Enesco’s Cantabile et Presto or the third movement interludes of the Hindemith Sonate, the pinky should move in a curling motion toward the palm rather than a sideways motion toward the third finger.

On the technically complex passages in the last movement of Ibert’s Concerto the fingers tend to slap the keys. This is corrected by keeping the fingers close to the keys and practicing the passage with so little finger pressure that all key noise is eliminated.

Work on any change of hand position or flute alignment while working on long tones or slow scales. Practice simple exercises of one or two-octave scales, arpeggios, and scales in thirds while making these changes.

With a mirror in the practice room students should check the hand alignment often. Each player has slightly different hand positions and body alignment that when used correctly lead to less frustration and a fluid finger technique.