I began experimenting playing whistle tones (also called whisper or flageolet tones) in my warmup recently. I had been going through a period where I was pushing too much to find the sound, and wanted to find a different way to explore sound production. The spark of inspiration occurred while I was re-reading the warmup section in Thomas Nyfenger’s book Music and the Flute. This sentence caught my eye, “The whistle tone is important as a warmup for the embouchure, because the eye is incapable of evaluating accurately the hole size or angle of air on such minute levels of variation…so we turn to the (whistle) tone, which requires relaxation as well as the proper angle of air.”

I was intrigued. In the past I had experimented with whistle tones as an extended technique, but had never used them on a regular basis in a warmup routine. As I began playing these lovely, quiet, high tones, I felt more relaxed and my use of air was much more productive – just as Nyfenger had said. I was curious to discover more whistle tone exercises for use in my own warmups, as well as with students. What follows are some tips and exercises I have found or written.

Helen Blackburn, flute professor at West Texas A&M, provides simple and clear instructions about how to produce whistle tones.

• Drop the jaw (stretch the chin away from the nose – far!)

• Roll out – FAR!

• No pressure with the left hand.

• Release upper lip away from teeth. Use your “beak” to aim the air.

• Feel the air travel on the inside wet part of your aperture.

• If you hear air, you are blowing too hard.

• If you are having a hard time finding the whistle tone, try fingering the 3rd octave note, but play as if you are playing a note 3 octaves lower – ppppp – just fogging up the embouchure plate.

• It may also help to try to whistle and/or sing the note you are aiming for.

• Have patience. This is the zen part – if you are trying the right way, you are getting the full benefits.

• You will improve every day. The harder you work, the fewer results you will see. Let go and surrender.

• Stop if you get frustrated.

Blackburn mentions whistling or singing the note. This helps because the tongue is placed in a good position for producing whistle tones, and the loudness of whistle tones increases with a correct tongue placement. You can also experiment with vowels to further assist in the shape of the mouth and throat. Wil Offermans, flutist and composer, suggests vowels like “ee/cheese” and “i/ship” for higher whistle tones that use a relatively small mouth cavity and vowels like “aw/awful” and “ah/father” for lower whistle tones that use a wider mouth cavity.

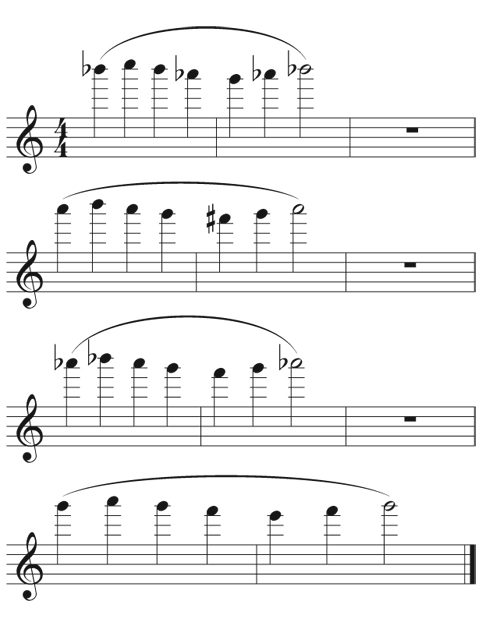

John Krell writes in Kincaidiana that William Kincaid had his students play whistle tones as long tones, sustaining them for up to ten seconds or more. I took this idea and combined it with the first exercise in Marcel Moyse’s De La Sonorite. Play the following exercise all in whistle tones, holding the first note under the fermata for one full breath. Play these without tongue at first, adding a light tongue when comfortable.

Another good beginning exercise is Peter-Lukas Graf’s “Ding Dong” exercise, originally found in his book Check-up, and adapted by Helen Blackburn. I expanded the idea of using familiar melodies as whistle tone exercises. This exercise is to be played all in whistle tones.

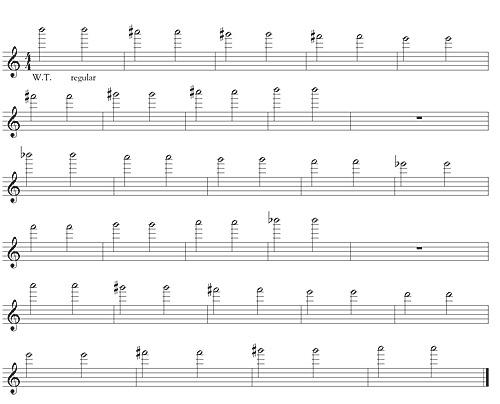

One could also practice alternating playing a whistle tone and then a normally blown note. Sustain a whistle tone (pianissimo) and then play the normally blown note with the same embouchure and angle of air (using regular fingerings for both) and increase the air pressure. Robert Dick, American flutist and composer, explains the goal is to reduce the amount of lip motion between the whisper tone and regularly blown notes, to a minimum. He adds, “A good way to think of the difference between the whisper tones and normally blown notes is that in the normally played high notes, the air plays a role in supporting the lip opening, while in the whisper tones, the same opening must be made and held open by the lips without any help from the air stream.”

I developed the following exercise to explore this idea. Play the first note as a whistle tone, pianissimo, the second as a regular tone, fortissimo, using regular fingerings for both. Play without tongue, breathe as needed.

To challenge yourself even more, you could practice very low whistle tones as Helen Bledsoe suggests. She writes, “Work on controlling a slow air stream by practicing very low whistle tones. Your embouchure has to be very steady because there is little air behind it to support it. (Patience: It took me a long time to get to Low C!) It may help to think about having a “tall embouchure” (very open in the middle). It may also help to think of having a cushion of air behind your lips (i.e., your lips are not too flat against your teeth) and to relax your jaw.”

To sum up, as part of a daily warmup diet, practicing whistle tones gives flutists the opportunity to slow down the process of tone production and explore the “minute levels of variation” that Nyfenger wrote about. In addition to an improved understanding of what the embouchure is doing, there is an increased sense of relaxation and wonderful lessons in patience. I highly encourage everyone to use whistle tones in their practice and in teaching.

Resources

“H.B.’s Super-Duper Zen Yoga Warm Up,” by Helen Blackburn. http://www.

depts.ttu.edu/music/flutestudio/downloads/

ResourceLinks/H.B.%27sSuper-DuperZen

YogaWarmUp.pdf

“Some Basics of Extended Techniques” by Helen Blesdoe. http://www.helenbledsoe.

com/ETWorkshop.pdf

Tone Development through Extended Techniques by Robert Dick

Music and the Flute by Thomas Nyfenger

For the Contemporary Flutist by Wil Offermans

Kincaidiana by John Krell

Music and the Flute by Thomas Nyfenger

Laura Lentz is a flutist and studio teacher based in Rochester, New York.