Every flute choir can play in tune. Young, old, two flutes or 60 flutes, they all can play in tune. A flute choir that has worked on intonation in every rehearsal will play musically with more resonance. Groups should tune chords, know the flute’s pitch tendencies, make instantaneous adjustments, and always tune to the bass note.

Initial tuning

Ideally directors should tune each member of the ensemble to an A individually before the rehearsal begins. Tuners can also be set up around the room, or a tuner can be passed around at the beginning of the rehearsal as well. This ensures that everyone begins at the same starting point.

Tuning everyone at the beginning of rehearsal to a flute pitch, as opposed to a tuner, may work well for experienced players but accomplishes little for young or inexperienced players, who are often unable to hear the correct pitch when many flutes are playing at the same time.

Once the initial tuning is complete, further adjustments are made for each chord with the embouchure and the air stream direction. Flute choir members should not re-adjust their headjoints for subsequent intonation corrections unless they find themselves adjusting in the same direction for every chord. With a little practice even beginners can learn to change the direction of the air stream to raise or lower pitches. However, they will not learn to make these adjustments if they have never been asked to try!

Learning to Listen

The following techniques can be used on any piece at any time, but it is easiest to work on intonation with a piece that has sonorous chords or basic harmonies.

To begin, hold the first chord of a piece until everyone can hear whether it is in or out-of-tune. If it is out-of-tune, stop; build the chord from the bottom up. Draw everyone’s attention to the bass note as they add their note to the sounding chord. For purposes of keeping a flute choir in tune, the bass is always right, even when it is wrong. In addition, the bass note should be everyone’s reference pitch (and not a personal tuner or stand partner), to make sure that everyone is adjusting to the same pitch. Now as each part joins the tuning chord and adjusts to the bass note, listen carefully for waves in the sound that don’t belong. Use the tuner to solve problems of individual pitches or for players who are having difficulty finding the correct pitch.

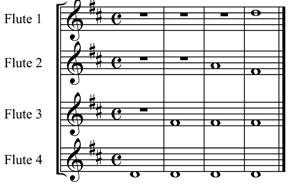

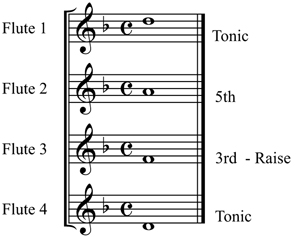

Tuning chords by stacking parts from the bottom up is one option:

Always draw attention to the bass note.

It’s right, even when it’s wrong.

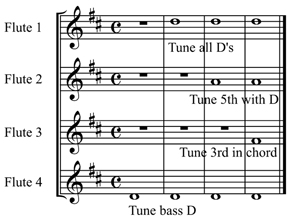

Another option is to start from the bottom, but tune notes of the same pitch together. For example, if the bass part has a D and it is the root of a D-Major chord, hear and tune the bass Ds first and then add all of the Ds in the other parts– each octave separately. Once all of the D’s are in tune, add the As (the 5th); finally, add the F sharps (the third).

Continue to draw attention to the bass.

When the chord is in tune, hold it so that everyone can hear how it sounds. It will ring clearly and vibrate beautifully. When the ensemble can play the chord in tune after holding it, stop and start the chord several times until it begins in tune without having to hold it.

Tuning one chord will help the entire piece, but continue to strengthen the group’s intonation by tuning individual chords as you work through the composition. If the chord you just tuned repeats in the music within a few beats or measures, tune the same chord again with its different voicing.

Next connect the tuned chords with the music in between them, lingering on the designated chords until they settle into focus. For the time being, ignore any intonation problems that might arise between the tuned chords.

Another way to practice intonation is to tune the first chord and then move to the second one, omitting any notes that do not fall on the beat. Do this with each beat for the first four measures. Then go back and play the same four measures as written – slowly first and then in tempo.

When working on intonation in larger sections, try tuning the first chord of each measure within the section. You can also choose strategic chords within the section. Be flexible and adapt this idea to fit the composition’s style. Then play the section through, landing on those tuned chords momentarily before moving on. Allow the ensemble time to settle in on those chords before continuing. Then go back and play the section in tempo. After the careful tuning has been done on a passage, in the future, simply work one or two chords in that passage and offer reminders to listen to the bass.

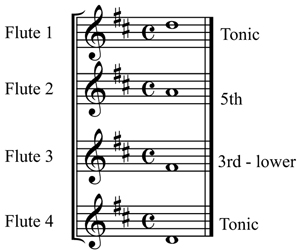

Note that when tuning, the third degree of the chord may need to be altered in order to make it sound more in tune. For more extensive information on this, see Trevor Wye’s Intonation and Vibrato Practice Volume 4.

For instance, the third degree of a major chord should be lowered a bit to be in tune. If you tune just the third of a major chord with a tuner, it is necessary for it to be flat on the tuner in order for it to be in tune in the chord. This is a matter of equal and just temperament. (see Wye, page 11).

The third of a minor chord, on the other hand, needs to be raised a little.

While tuning each individual note of a triad with a tuner makes the chord sound more in tune, adjusting the third in this manner gives chords more resonance. It may seem complicated at first, but with practice it can become second nature and happen automatically.

Singing

Singing helps any intonation session. When tuning chords, ask members to sing the bass pitch and then the pitch that they play. They might sing do-mi or sol-do or do-mi-sol. Directors can also sing the two pitches and ask the group to sing them back. After players sing the correct pitches, they should play them. The mystery of music takes hold at this point, and intonation of that interval miraculously improves!

In the previous example the bass flutes have both the tonic and the bass note. Many times in music, however, the bass flute does not have the tonic of the triad. It is still helpful to sing the bass pitch first and then the upper pitch, because the upper pitch should match the lower one – not visa-versa.

Tuning for practice in warm-up

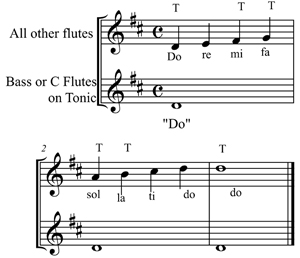

There are some general warm-ups that can help flute choir members hear intonation problems and adjust more quickly. Using the key of the piece that is about to be played, ask players to play the first, third, or fifth note of the tonic chord. It is simpler at first to have all of the bass flutes play the tonic, which has been tuned with a tuner. With the bass flutes on the tonic, add everyone else. Give them a few seconds to find the pitch. If it does not settle in, tune each note until the chord sounds perfectly in tune.

Although not everyone will hear the problems of an out-of-tune chord at first, they will quickly learn. Next, ask players to choose a different note of the chord. Tune the chord again, just as before. When the chord is in tune, play it several times until the choir can begin with the chord in tune, and not just settle in after a few seconds.

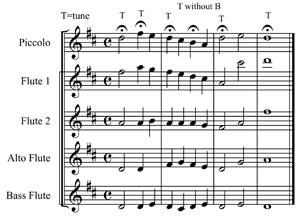

Another warm-up is for the bass flutes to play the tonic pitch while everyone else moves up a major scale. Stop to tune the consonant and perfect intervals (3rds, 4ths, 5ths, 6ths, and unisons/octaves) on the way up as indicated in the example below. If intervals remain out-of-tune after they have been held for a few seconds, sing the intervals from the bass to the soprano. For instance, if the F# is out-of-tune, ask the group to sing Do-mi. Then play the interval again, everyone on their own note.

Finally, explain pitch tendencies and state them often until everyone knows that flutes are generally sharp on C sharp and D. Top line F and B flats are flat. High notes are sharp, with the exception of third-octave B flat, which can be flat. Low notes tend to be flat, as do soft ones. Loud notes can be sharp, etc. Knowing pitch tendencies helps players make instant judgement calls about which direction to move, particularly when they are unsure from listening which way to go.

The beauty of taking time to tune passages carefully in rehearsals is that a flute choir will continue to play those passages in tune in the future with perhaps just an occasional reminder to listen to the bass. Players’ pitch memory takes over in those passages and there will be a marked improvement that cannot be achieved by repetition only.

Improving intonation takes the most time with new music, and then less as players become more familiar with the music. Improving intonation also takes more time with new members, but as they become familiar with the process and begin to make adjustments quickly it takes less time. By working on intonation, the group will improve in such a way that everyone notices. With practice, members of a flute choir soon begin to realize when they are out of tune, listen to the bass to find the reference pitch, and learn to self-correct.

Ignoring intonation problems with the hope that they will go way is a waste of time. Like everything else, intonation only improves with practice.