Players of the modern flute invest their time in strengthening their performance skills and expanding their repertoire. They may also read books and articles about the development of the flute to increase their overall understanding of the instrument’s modern construction. Flutists may further enhance their appreciation of the flute through artwork. Throughout the centuries, artists have often featured the flute in its varied and ever changing role in society.

Two artworks that are probably the most recognizable to flutists are the engraving by Bernard Picart on the cover of Jacques Martin Hotteterre’s Principes de la flute traversiere (1707) and Adolph Menzel’s painting The Flute Concert of Sanssouci (1851), which depicts Frederick the Great playing the flute. In addition to these two works, there are many others that might be of interest to flutists. From images of the flute found in early cave paintings of 30,000 BCE to images found in contemporary works, much can be revealed about the development of the flute and how it is influenced by social structure and historic or political events of the time. The evolution of the flute, as observed in visual arts, helps us understand how and why it developed into the instrument that we play today.

Since the most significant changes in the development of the flute began in the Baroque period, the flute depicted in artwork of this period is of great historical importance and interest. It is also interesting to note the independence of the flute and recorder during this period. The instruments have distinct characteristics and are used to perform different types of music for different occasions.

The Baroque style in art began in Rome with a revolutionary young artist named Michelangelo Merisi de Caravaggio (1571-1610). One of his music paintings is titled The Lute Player (1596).

This painting depicts a musician playing the lute; on the table are music books and a violin. Another variation of this painting by Caravaggio includes a miniature spinet and a flared-bell recorder. In his short life span, Caravaggio revolutionized the concept of painting from technique to subject matter. What Caravaggio creates is a moment in time in which the viewer is allowed to participate and listen to the music being played. The darkened background keeps the viewer’s eyes on the foreground and the action that is occurring. No longer is a background needed to create the illusion of space as was typical of the Renaissance – the emphasis is now on the foreground. The diagonal line of the lute and cast shadows keep the eye moving around the foreground plane. The mouth of the lute player is open – suggesting the action of singing. This is an active painting. Many followers of Caravaggio traveled to Holland and settled in the Utrecht region. From there, Caravaggio’s style was picked up by the Dutch artists.

Dutch artists incorporated flutes into their artwork for many reasons. During the early 17th century, Holland became one of the largest and wealthiest provinces in the Netherlands. After Spain recognized Holland’s independence in 1609, Dutch artists began to express their patriotic spirit in paintings with subjects that emphasized cheerful events. Music was frequently depicted as an activity of continuous enjoyment and leisure, and images of flutes appeared in many of the artists’ works. These works usually show the flute being held or played by middle-class boys dressed in ordinary garments. Music is not seen as an elite activity but rather as an activity for all to enjoy. The flute soloist or chamber ensemble with flute is depicted as a form of personal entertainment. The scenery is simple and a mood of happiness and optimism is created. Flutes in these paintings represent a desire to enjoy the simple things in life.

Examples of two Dutch artists who reflect the influence of Caravaggio’s style and include the flute in everyday scenes are Hendrick Terbrugghen (1588-1629) and Judith Leyster (1609-1660). Terbrugghen’s two related paintings, Boy Playing a Recorder (1621) and Boy Playing a Fife (1621), show middle class boys playing flute-related instruments. Following the style of Caravaggio, Terbrugghen shows half-length figures highlighted against a plain background, but each represents a different purpose for the flute. The boy with the fife is in a striped soldier’s costume and represents the urban and the military. The boy playing the recorder is in a shepherd’s dress and represents the rural and pastoral nature of the flute.

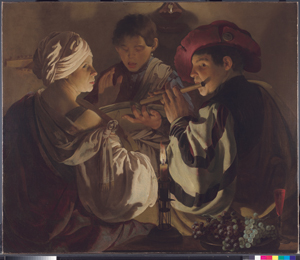

Another one of Terbrugghen’s paintings, The Concert (1626), shows a group of three ordinary youths practicing their music by candlelight. Terbrugghen’s connection with Caravaggio is observed through his setting of these candlelit half-length figures against a lighter background. They are crowded together close to the edge of the canvas so that attention is immediately drawn to them. The instrumentalist is performing on a transverse flute – in contrast to the recorder and the fife seen in his earlier paintings.

Judith Leyster was influenced by the work of Terbrugghen. Her popular painting of Boy Playing a Flute (c. 1630) shows a young middle-class boy playing a transverse flute. On the wall behind him hang a violin and a recorder. The early 17th century was a period in which various types of flutes and recorders are depicted in paintings before the development of the one-keyed Baroque transverse flute around 1660 by Hotteterre.

In addition to the role of the flute as a symbol of happiness and leisure, the flute was included in many still-life works. Seventeenth century Dutch artists were famous for their lifelike paintings of still life. Before 1650, more common objects of glass, pewter and earthenware were depicted as opposed to the more wealthy silver, gold, and porcelains seen in later works. The Dutch painters often introduced symbolic and allegorical meaning into their compositions, perhaps wishing to elevate the moral value of their work and appeal to a more affluent and educated patronage.

In many of these works, the flute conveys various meanings. An example of a still-life work is Still Life with Musical Instruments (1623) by Pieter Claesz (1597-1660), which depicts a table with a partly sliced loaf of bread, a tortoise, a glass, watch, books, paper, lute, cello, recorder and other musical instruments.

The vanitas is a genre of still-life painting also popularized by the Dutch. Oftentimes depicting a flute, these paintings use common objects to represent the transience and beauty of life. Evert Collier (1640-1708) in his vanitas painting Still Life with a Volume of Wither’s ‘Emblemes’ (1696) depicts a draped table with various objects. The skull and hour glass represent the inevitability of death while the musical instruments, sheet music, fruit, silver goblets, and jewelry represent the pleasures of life. The book is opened to a poem based on mortality. The Latin scripture seen in the left corner reads: “Vanitas Vanitatum, Omnia Vanitas,” which translates as Vanity of vanities, all is vanity (Ecclesiastes 1:2). All these items reflect the uncertainty and shortness of life. The flute, along with other common objects, reminds the viewer that death is certain, and earthly pleasures are fleeting.

Tronies were paintings by Dutch artists usually based on living models. They were not portraits but were intended to be studies of expression and character. They were sold in the open market, so the artist was free to choose his subject and style of dress. Oftentimes, the subject would be holding a musical instrument such as a flute or recorder. Exotic looking garments were frequently used so that the artist could show off his technique. Formal portraits were quite different, preserving the likeness of the individual for posterity and creating an image of pride and social position. A tronie attributed to Jan Vermeer (1632-1675) is Girl Holding a Flute (c. 1665).

Vermeer shows a young girl dressed in elaborate clothing holding a recorder. Before the 1650s, the middle class was depicted in ordinary garments, but after the 1650s, the middle class was dressed more elaborately showing the wealth and commerce that arrived in Holland after 1650. Not much is known of Vermeer and his subjects, but he depicted this middle-class Dutch woman and her personal items in great detail – with her exotic Chinese hat and drop-pearl earrings set against a tapestry background. Vermeer continued using the spotlight technique of Caravaggio and the use of diagonals to reach out to the spectator.

In addition to the paintings and artists already mentioned, there are many other Dutch Baroque artists who use the flute in their works. These works are also worth exploring. Such artists (with approximate dates) include Frans Hals (1580-1666), Dirck Hals (1591-1656), Jan van Bijlert (1598-1671), Jan Miense Molenar (1610-1668), Benjamin Gerritsz Cuyp (1612-1652), Govert Flink (1615-1660), Abraham van Beyeren (1620-1690), and Gerard de Lairesse (1640-1711).

The flute has developed technically but also symbolically throughout the centuries. It has been associated with rituals of death from tomb decorations to vanitas and tronie paintings. It has been part of celebrations and festivals. It has been a social equalizer and status symbol. During the 17th century, it helped characterize a country’s independence and advances in economic wealth. The imagery of the flute has played an important role in the development of society and social classes.

References

Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi de Caravaggio). Lute Player. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum. Photo by Vladimir Terebenin, Leonard Kheifets, Yuri Molodkovets

Hendrick ter Brugghen. Knave Playing a Recorder. Gemaeldegalerie Alte Meister, Kassel, Germany/©Museumlandschaft Hessen Kassel/Ute Brenzel/The Bridgeman Art Library

Hendrick ter Brugghen. Knave Playing a Fife. Gemaeldegalerie Alte Meister, Kassel, Germany/©Museumlandschaft Hessen Kassel/

Ute Brenzel/The Bridgeman Art Library

Hendrick ter Brugghen. The Concert. Bought with contributions from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, The Art Fund and The Pilgrim Trust, 1983 © The National Gallery, London

Judith Leyster. Boy Playing the Flute. Photo © Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

Pieter Claesz. Still Life with Musical Instruments. Louvre, Paris, France/

Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library

Edward Collier. Still Life with a Volume of Wither’s ‘Emblemes’. © Tate, London, 2012

Jan Vermeer. Girl Holding a Flute. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington