When I recorded Lowell Liebermann’s Sonata Op. 23 in 1993 the work was just five years old. Making that record was a thrilling adventure and musically trail-blazing for me. Flutist Paula Robison had recognized the young composer from New York City as a rising star and commissioned the new flute and piano sonata. She gave the first performance on May 22, 1988 at the Spoleto Festival in Charleston, South Carolina. The flute community was swept off its feet by this powerful and boldly neo-Romantic work. The rest, as we know, is the proverbial history. The Sonata became one of the most studied, performed, and recorded works in late 20th-century flute repertoire. Though numerous fine chamber works for flute came from the 1970s and 1980s, none after Copland’s Duo (1971) filled the spot of a flute and piano duo or sonata of major proportions until Liebermann’s Sonata. In 20 short years it has achieved the status of a classic.

At the time of my recording, the Sonata was still relatively new and barely recorded. It was considered extremely challenging, both technically and musically. This has not changed; what has changed is the rising level of competition among younger and younger flutists and, consequently, the emergence of a new performance standard at the teenage level. Liebermann’s Sonata now appears on the National Flute Association’s High School Soloist list, and we can be sure that it will be masterfully played by the top young flutists in the country.

In considering beneficial etudes and other exercises for learning the Sonata, I find it impossible to separate technical issues from musical ones. The biggest challenge facing young high school or college players is understanding the dramatic significance of Liebermann’s instructions in the score and finding a way to execute them at a level of musical maturity that may belie their years.

The first movement is surprisingly like that of Copland’s Duo, in terms of its multiple sections and very precise performance markings. As with Copland, there are at least eight sections defined by tempo changes and verbal instructions. A few of the Italian phrases will send you to the Italian dictionary and are important for interpreting the music’s character. As we examine each part of this movement individually, however, we must remain aware of the overall intensity of the whole. Here we depart from the Copland analogy because this work is not a series of scenes but a personal outlay of emotion that moves between the softest hints of something under the surface to wild release of expressive tension. How we maneuver through this emotional landscape determines whether the movement results simply in big ups and downs or in a cohesive journey that is affective as well as it is virtuosic.

First Movement

The Opening

.jpg) The opening takes a standard four-bar melodic phrase and plays it over the piano’s hushed backdrop of eighth notes that set up an almost too-sweet atmosphere, one that will evolve dramatically. The initial tempo marking of 40 to the quarter note and the dolcissimo possible (as sweetly as possible) put a strain on the performer to exercise supreme breath and lip control over the phrase, to maintain simultaneously the pp dynamic and exquisite tone color needed. Liebermann later revised the tempo upwards after concerns from performers that 40 was too slow to carry out the phrase successfully. While I agree that the original tempo may be extreme, its role of drawing out the line and spinning the breath to its limits must be preserved. This exertion is what creates the apprehensive note in an otherwise innocent-sounding melody of effortless beauty.

The opening takes a standard four-bar melodic phrase and plays it over the piano’s hushed backdrop of eighth notes that set up an almost too-sweet atmosphere, one that will evolve dramatically. The initial tempo marking of 40 to the quarter note and the dolcissimo possible (as sweetly as possible) put a strain on the performer to exercise supreme breath and lip control over the phrase, to maintain simultaneously the pp dynamic and exquisite tone color needed. Liebermann later revised the tempo upwards after concerns from performers that 40 was too slow to carry out the phrase successfully. While I agree that the original tempo may be extreme, its role of drawing out the line and spinning the breath to its limits must be preserved. This exertion is what creates the apprehensive note in an otherwise innocent-sounding melody of effortless beauty.

One of the best exercises I know for the first four bars is to practice them pp an octave higher, which provides the faster air speed and more concentrated embouchure position to produce the slight spin and support necessary in the lower octave to grip the sound. I use the image of finding my way through a dense fog cutting carefully with a small, powerful band of light. How this translates to a specific mood is your choice, whether it’s rich, pale, dark, hard, soft, etc. What is crucial is deciding upon the mood and selling it to the listener.

Experiment with alternate fingers for the high notes in the first section (F# in m.7, A and B flat in m. 15-16), to gain a more transparent sound. For F# and G, use the pinky on the low C# key. For A to B flat, use the same low C# plus the thumb-Bflat key, then move to B flat with left first finger, hold thumb Bflat and right first finger, add the first trill key and the F# key.

Breathing is the other factor to consider in the opening phrase. In most performances I have heard, flutists breathe after the D#, halfway through the phrase. I urge you to play the entire phrase in one breath, which is much more effective in maintaining the suspense inherent in the line. This may be the determining factor in your tempo, which should work as long as you are somewhere between the 40-60 metronome marks.

To practice extending your breath, play Taffanel-Gaubert’s Daily Exercise #4 pp with a concentrated sound at half note = 50, as with the Sonata opening, and go absolutely as far as your breath will take you – to the point of losing the sound but still pushing out the last bits of air. Next time try to surpass your previous limit, always extending to the point of emptying your air supply completely. Then try the same thing with the Sonata, playing beyond the point of good tone, until you make it to the end of the phrase. Then work to extend only to the end of your desired sound; you should feel air pressure all the way through but not the strain you may have felt while pushing past your safe limits. This is also, by the way, a good slow-motion approach to Taffanel-Gaubert’s Daily Exercise #4, to examine steady air flow and consistent sound through the scale pattern. It is effective when done at the loud end of the dynamic spectrum as well.

The Second Section

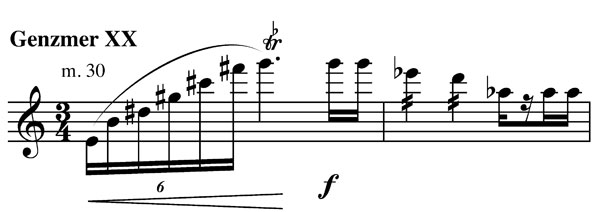

The first emotional outburst occurs at measure 30 and requires sudden force and intensity in all three registers. Two etudes from Harold Genzmer’s Neuzeitlche Etuden (Schott, vol. 2) are very useful for developing a loud, focused tone in all registers and have a fierceness of spirit similar to that in bar 30.

.jpg)

Etude No. XXII (22), marked Feroce, begins in the third octave and works its way down to the first in varying degrees of forte and accented staccato articulation.

Etude No.XX (20) has more interval leaps, trills, and upward runs, all of which mirror the second outburst in the Sonata between bars 55 and 60.

There are moments in both of these sections when flutists feel overpowered by the piano’s thundering away in the style of a huge Liszt piano etude, which is part of the reason this work is so attractive to us. So much of our repertoire is light and airy. Having a true Romantic work in the full-blown manner and modern harmonic language of the late 19th-century composers fills a large gap in the flute sonata repertoire. Most of Liebermann’s scoring is well-balanced between flute and piano, and my attitude about the moments when he pulls out all the piano stops is to play into the Romantic thunder and not worry about being covered. If you keep maximum focus, especially in the descending scale in bar 32 and the sextuplet runs in 56-7, the effect will be that of an orchestral flute adding to the overall texture – something akin to playing big tutti passages in a Tchaikovsky symphony.

The Transition

.jpg) Measures 36-48 are a transition to the next major section. At Tempo I in bar 36, Liebermann indicates the original tempo quarter=40. At the Piu lento in bar 42 he changes the beat unit to eighth =72. Consider the subtle difference between how you would play the 16ths leading into bar 39 in quarter pulses as opposed to the 16ths leading into 41 with an eighth-note pulse. Then consider the Piu lento: eight beats per measure ma cantando (but singing).

Measures 36-48 are a transition to the next major section. At Tempo I in bar 36, Liebermann indicates the original tempo quarter=40. At the Piu lento in bar 42 he changes the beat unit to eighth =72. Consider the subtle difference between how you would play the 16ths leading into bar 39 in quarter pulses as opposed to the 16ths leading into 41 with an eighth-note pulse. Then consider the Piu lento: eight beats per measure ma cantando (but singing).

I often hear performances in which the pulses are reversed, eighths for the first figure (which is certainly grouped that way into two-note slurs), and quarters for the following phrase, which make it easier to keep the singing quality and get to the end of the phrase. Liebermann’s more natural transition from quarter to eighth pulse, and the additional weight in the phrase at Piu lento are important for preparing the next section at 49, especially through the incredibly long Grand Pause measure at 48. It takes courage to play this slowly and to hold breath and suspense during such silence, but you will have the audience mesmerized if you do it with the continuity and smooth intensity of line that Liebermann indicates..jpg)

The Third Section

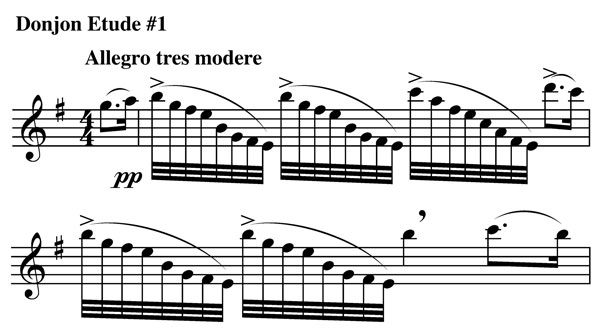

The section starting at m. 49 with its tight, dotted figures and long buildup takes great discipline of airstream and fingers. Though stylistically from another period, Donjon’s Etude de Salon #1, Elegie-Etude, is effective for achieving fluidity with the fingers in the same legato context as the Sonata.  Trever Wye’s Digital Exercises from his Advanced Practice Book are also excellent for exercising the common trill-fingering patterns and learning finger independence.

Trever Wye’s Digital Exercises from his Advanced Practice Book are also excellent for exercising the common trill-fingering patterns and learning finger independence. .jpg) In Italian Liebermann asks us to start hesitantly and grow little by little but to remain rhythmically accurate: p, esitatante poco a poco f e ritmico. The magic at the start of this long crescendo lies in the performer’s ability to begin as quietly as humanly possible and to play the rhythms so tightly and smoothly that they are just tiny ripples under the airstream’s surface. Stay quite soft until bar 53, then begin the big buildup dynamically. The goal is to have m. 55 truly sound like an arrival and not simply another loud section.

In Italian Liebermann asks us to start hesitantly and grow little by little but to remain rhythmically accurate: p, esitatante poco a poco f e ritmico. The magic at the start of this long crescendo lies in the performer’s ability to begin as quietly as humanly possible and to play the rhythms so tightly and smoothly that they are just tiny ripples under the airstream’s surface. Stay quite soft until bar 53, then begin the big buildup dynamically. The goal is to have m. 55 truly sound like an arrival and not simply another loud section.

Two final often ignored score details occur in the first movement from m. 60 onwards. At m. 62 the marking is estatico (ecstatic) under an eight-bar phrase that leads us to the final section. What this emotional state means to you and how you give it meaning will separate this phrase from the other lyrical ones in the movement. Vibrato speed, higher or lower partials in the sound, directional or more static line are some of the elements to consider in deciding how to deliver this phrase. It is a small indication that often gets overlooked or is not pursued far enough to make a difference to the listener.

The final two lines of the movement, where the dotted figure returns, bear close scrutiny for phrasing. Many interpretations of bars 97-99 keep the passage connected by breathing before the triplet leading into the next measure, but the phrase marks in each measure go to the end of the measure, then start again in the next. By playing the measures as indicated, you break up the line, as though being stopped in your tracks and having to try again. This is what the composer intended, in my opinion, and it adds to a much more interesting interpretation of the ending. Phrase off the end of the triplet enough to make a space for a breath and come back in without letting another beat occur. This discomfort in playing the phrase can work to your advantage musically.

The long, slow wind-up to the last note is marked lento, a piacere. Emphasis should be on the latter two words, at your pleasure, and will provide the freedom to shape bar 100 as you wish and defy the listeners’ expectations.

Movement II

The second movement, Presto energico, needs practically no musical discussion as it is a tour de force from start to finish. The main difficulty, apart from the notes themselves, which include some very awkward combinations that are harder for those who depend on the thumb Bflat, is passing from triple to duple back to triple meter again. Etude #9, rapido e brillante, from Karg-Elert’s Caprices Op. 30 is helpful because it goes back and forth between 6/16 in 2 beats per bar and one beat in 38. .jpg) The etude is a bit easier than Liebermann’s passages because of the slurring pattern in the 38 bars of two-note groupings. In the Sonata each time the triple-to-duple phrase enters (bars 19-22), the articulations really emphasize the groups of three with accents and slurs in the 12/16 and the groups of four slurred 16ths in the 3/4 measures. The natural tendency is to slow down the groups in the 34 measures, and then the return to groups of three in bar 22 seems too fast.

The etude is a bit easier than Liebermann’s passages because of the slurring pattern in the 38 bars of two-note groupings. In the Sonata each time the triple-to-duple phrase enters (bars 19-22), the articulations really emphasize the groups of three with accents and slurs in the 12/16 and the groups of four slurred 16ths in the 3/4 measures. The natural tendency is to slow down the groups in the 34 measures, and then the return to groups of three in bar 22 seems too fast..jpg)

You can also write out your own exercise for these measures by continuing groups of three in 20-21, retaining the articulations but accenting in threes. You can group bar 19 in fours and continue in fours to the 9/16 bar, when you can group 4+2+3. Later in the movement when this juxtaposition occurs, the piano has more continuous 16th-note motion to steady the flute line. One reason the first presentation is so tricky is because the piano plays only chords in bars 20-21.

The extended lyrical section requires a broad wash over the piano’s insistent triplets but with an absolutely steady tempo; don’t give in to the temptation to slow the quarter-note triplets. Basically, the entire movement’s tempo does not change one iota and thus has a kinetic force that gathers strength by its simple presence and repetition. The final section from bar 165 to the end should be somehow even more than what preceded it. For the repeated E flats in 165, I suggest using the D-Eflat trill fingering of D plus the first trill key. This produces a raw, metallic sound, not pretty but very loud and penetrating and better in tune than the regular E flat at the fff level. With the groups of seven-minus-one in the last two lines, I start on a “T” and end with a “K” articulation. You get more sound at the start of the group, and you have a slightly easier time getting to the triplets three bars from the end. You might also wish to try the D-plus-trill key for the last D#’s.

Technical mastery of this work depends on a commitment to practice long hours intelligently and with the help of a great teacher. Musical mastery is more indefinable but can also be practiced, by attending to the details in the score and by searching in yourself for the reasons you are moved by this great work. Make it your own statement – one that will ring true within your own heart and mind.